Are They All Wrong?

The Most Rev. Albert Power, S.J.

Christianity is an historical religion—it centers around an historical Person—it appeals for credentials to historical documents; and, therefore, all the arguments in its favour must, to some extent at least, be drawn from history. Still a distinction can be made between the argument for Catholicism which deals with the nature of her internal life and organization—her doctrines, Sacraments, and legislative system; and the argument which tells the story of her external life—of the men whom she has found to champion her cause, of the battles she has fought, the foes she has met, the wounds she has received, the victories she has won; and from this story of her march down the ages draws conclusions as to the validity and reasonableness of her claims.Both arguments appeal to history, but the former may involve much metaphysical and theological speculation, whereas the latter is purely historical. It is with this latter we are dealing in this booklet.And it is my purpose briefly to indicate some lines of argument in favour of Catholicism which may be drawn from a consideration of the number and nature of those who, all down the centuries, have been her staunch supporters; the character of her enemies; the opposing systems and organization she has met and conquered; from the steadfastness with which, in the midst of every conflict, she has clung to the teaching of her Founder; and the wonderful life and vigour, unity and strength which are still her characteristics after nineteen centuries of strenuous existence.

Rationalists

There is in the world a certain body of men who call themselves Rationalists. They profess to take their stand on reason alone, to look to reason as the final Court of Arbitration, and refuse to allow any principle of authority or religion to interfere with its findings. That is what they profess. But they begin by excluding a priori the possibility of miracles, of a Divine Revelation, of supernatural religion, even though evidence for these things be available which appeals to reasonable men. That there must be such evidence seems clear from the fact that millions of reasonable, well educated, scientific, up to date people have accepted, and do accept, miracles and Revelation as actual facts, and regulate their lives on the supposition that they are facts.

Now, in contradistinction to such pseudo rationalists, I assert that history proves that Catholics are in the true sense of the term Rationalists—that is men guided by Reason; and that the Catholic system is the only one founded on sound Reason—is the only system that fearlessly and frankly weighs all the available evidence and forms its judgement according to that evidence.

PART I.

No organization in history has had such a splendid line of defenders as the Catholic Church—from Paul of Tarsus, the first great Catholic Apologist, to the fine array of modern preachers, lecturers and writers, of every nation on earth, who are so busy in proclaiming their reasoned conviction that Catholicism is a true religious system.

When the test of Reason was applied to the pagan myths of Greece and Rome, belief in those myths crumbled away and disappeared for ever from the face of the earth, because such belief was founded on ignorance and superstition.

The same process we see going on around us today in the case of the various fancy sects that are for ever springing into being—flourishing a brief space, then disappearing forever. Have you ever heard, for example, of the “Deep Breathers”? They insist, I believe, not merely on the hygienic and lung-strengthening properties of deep breathing (in this we would not quarrel with them), but on the mystic and spiritual effects produced by taking a deep breath, holding it as long as possible, and pronouncing while so doing certain formulae.

Common sense—that is, plain reason—finally kills these fancy religions.

Not so with Catholicism. True reasoning serves simply to strengthen belief in the Catholic position. And for historical proof of this let us, in the first place, glance back over the century or so that has elapsed since the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829, and turn our attention to one small portion of the Catholic Church—namely, England.

By 1829, the Catholics in England, harried and persecuted for over two centuries, had reached a very low ebb in point of numbers and organization. But their courage was beginning to revive, they were coming more into the open and making their influence felt. And, behold! where, of all places in the world, did this influence of the old Faith produced the most noticeable results? Why, in the very home and sanctuary of Reason, the centre of learning and culture in England— namely, the University of Oxford. Almost immediately after the Emancipation Act of 1829, the famous Oxford Movement began. A few years later John Henry Newman, Fellow of Oriel College, published the famous Tract for the Times, No. 90—which one may regard as his first public step on the march to Rome.

Thirty years later, in 1864, Newman wrote his “Apologia,” the history of his religious opinions. The book was electric in its effect. It was a masterpiece of literature produced by the greatest living exponent of English prose—but it was also a work of close and intense reasoning, telling the world why John Henry Newman, at the age of forty-five had quitted the Anglican Establishment and embraced the Catholic Faith. It is a splendid exposition by a master mind of the reasonableness of Catholicism.

Newman’s “Apologia”

The “Apologia,” as all know, had an extraordinary influence in bringing people into the Catholic Church. Since 1845 the tide of converts to Catholicism, especially from the educated classes in England and America, has gone on increasing year by year. Many, perhaps most, of these conversions were the result of historical study; and as each submitted to the Church and made Catholicism the guide of his life, he became a new and living proof of the proposition that Catholicism is founded on reason.

For surely, when hundreds of thousands of people of every walk of life, of every rank of society, of all shades of religious upbringing and surroundings; educated people, many of them recognized as foremost authorities in historical, philosophic or scientific research, after long and careful investigation, in the bright noonday of modern culture and development when these people in ceaseless streams embrace the Catholic Faith, and when practically all these people not only persevere in their adhesion to the Faith, but deliberately state, after ten or twenty or thirty years of Catholic life, that they have never had a doubt or a moment of real intellectual discomfort in the profession of their Faith: and when they, furthermore, assert (as many have done) that the Catholic religion seemed to bring them an extraordinary sense of intellectual liberty, expansion of soul, light and strength, then, I say, the religious system that has such testimony in its favour must have strong, convincing arguments to justify its existence and to demonstrate its superiority over every other religious system in the world.

The First Catholic Evidence Lectures

So it is when we look back a hundred years and consider one small corner of the Catholic Church. Now let us look back not merely over a hundred or two hundred or five hundred years, but over nearly two thousand years of history—and what do we find? Generation after generation, century after century, tell the same story. Earnest, thinking, reasoning, learned people, men who did not want to be fooled and had no inclination to swallow idle tales, religious people whose one object was to make a right use of life, examined the claims of Catholicism, studied the arguments in its favour long and earnestly, and then gave their adhesion to it with wholehearted, unhesitating confidence. And the point I want to insist upon is that these people constantly appeal to Reason as the foundation of their faith and the grounds of their acceptance of Catholicism.

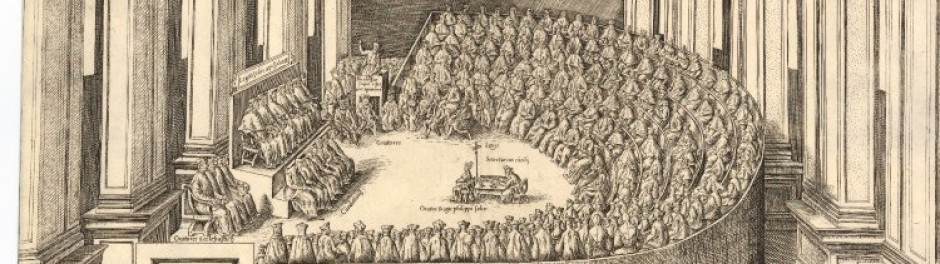

Go back right to the beginning. Think, for example, of the Apologists of the second century, say Justin the Martyr. We have two apologies, or, to use modern phraseology, two: “Catholic Evidence” lectures, presented by him to the Roman Emperor or the Senate about the year 150 of our era. Read those treatizes and you will find that Justin is constantly appealing to Reason in defence of the Christian Faith. He is, in fact one of the first who deliberately set himself to study the relations between Faith and Reason; that is, to defend our Faith by showing how it is based on Reason. Considering the pioneer work he did in this respect, I think St. Justin has strong claims to be regarded as the special patron of Catholic Evidence lectures, for he started the series of Public Evidence lectures of which our modern lectures are a continuation.

In his case these efforts to demonstrate Catholic Truth led to his violent death. He was martyred in Rome about 167 A.D. Whether similar results are likely to follow our efforts, time alone will tell.

Origen

A few years later than Justin we meet with two remarkable men in the great commercial city of Alexandria, both deep students, men of wide reading and extraordinary intellectual activity, Clement and his great pupil, Origen. Origen is one of the most remarkable men the world has ever known. He was the founder of Biblical Textual Criticism. He took extraordinary pains to get at the original Hebrew and Greek texts of the Bible, collecting and comparing manuscripts with the greatest diligence. He was a man of vast intellectual power and was deeply versed in all the philosophic and religious learning of the day, and he had at his disposal the great Alexandrian Library—the greatest collection of books in antiquity.

Both Clement and Origen carried on the work of Justin the Apologist—that is, they, too, set themselves to justify the faith of Catholics by appealing to reason and showing that the beliefs of the Catholic Church are founded on reason. Origen died A.D. 254. Exactly 100 years later was born the man who is regarded by many as the keenest and brightest intellect the Christian Church has ever known, St. Augustine, Bishop of Hippo. After wandering for years in the mazes of religious error, Augustine was at last caught by the beauty of Catholic Truth, embraced the Catholic Faith, and devoted some forty-five years of strenuous activity (till his death in 430) to the defence of that Faith. The numerous works he wrote in its defence have been a shining light in the Christian world ever since.

Now, when Augustine embraced the Catholic Faith he did not do so out of mere blind enthusiasm. In his youth he wandered far from the Church, in spite of the instructions of his saintly mother, Monica, plunged into the alluring speculations of Manichaeism, a form of that Persian dualism which in one shape or other has fascinated human minds from the days of Zoroaster down to our own. Augustine remained for years an adherent of this system; but gradually, step by step—aided by God’s grace—disentangled himself from its errors as well as from the meshes of sensual indulgence into which he had been trapped, and won his way to the full light of Catholic Truth.

We have the story of that great struggle and splendid victory told in words of incomparable beauty in his “Confessions,” one of the world’s greatest books.

The Weapon of Reason

What was the weapon by which this great man was forced to accept the truth of Catholicism? It was the weapon of Reason. God’s grace was, of course, there, helping, illuminating and guiding him, but Augustine, in the true and noble sense of the term, was one of the world’s great Rationalists; and, as a result of his reasoning, he embraced wholeheartedly the doctrine of Catholicism, as the only trustworthy religious system in the world. And here, perhaps, we may draw a comparison. Augustine may be called in a true sense the Newman of his age. The moral complexion of the early life of these two men was indeed very different. Newman’s youth was innocent; Augustine’s, unfortunately, was given over to sensual indulgence. But intellectually there is a remarkable parallel. Each had lived for years in heresy, and each came ultimately under the spell of the Catholic Church, was won by her beauty, and after a hard struggle surrendered entirely to her claims. Then each spent forty-five years employing in her defence glorious gifts of eloquence in speech and writing. Both were men intense in their devotion to Truth as Reason showed it to them. And because they followed that light, therefore, they embraced the Catholic Faith.

Moreover, each of these two great thinkers stood at a turning point in history. In Augustine’s day the Roman Empire was being shaken to its foundation by the invasions of barbarian hordes that were swooping down on the old decaying civilization, were destined, finally, to wreck it, and from the wreckage the nations of modern Europe were to develop. Newman also lived in the heart of a great Empire that, like the Roman, had set her giant footsteps on land and sea all round the busy world—and he, too, was living at a turning point of history, when new intellectual forces were rushing in to plunder the decaying intellectual civilization that had no strength to resist the onslaught.

A Turning Point in History

For Protestantism, at the beginning of the nineteenth century, was played out as a religious force. The Reformation had done its deadly work only too well. The old Catholic Faith had been swept away. The Catholic Church in England that had been one of the glories of Christendom—as its splendid monuments still testify—had dwindled to a handful of people cowering out of sight and practicing their religion by stealth. The Anglican Establishment, which had usurped the place of Catholicism, was so far as real inward religion was concerned, crumbling to pieces. The storm of so-called Rationalism was raging and rising in intensity. We know how that movement developed. John Stuart Mill, Herbert Spencer, Darwin, Huxley, Tyndall, and a host of others, in the name of science, swooped down upon the defenseless people of England— defenseless because they had been robbed of the protective armour of Catholic Faith—as the Vandals swooped on the Roman Empire. And the result was inevitable. Protestantism had not the strength to resist, with the result that today England is once more, to a large extent, a pagan country.

Augustine and Newman—two great men of reason—and both intense defenders of Catholicism, were separated by fifteen hundred years of busy life. Midway between them comes a man in some respects greater than either, Thomas Aquinas, the great Dominican theologian, whose intellectual activity and ceaseless toil in defence of Catholicism filled up a large portion of the thirteenth century.

Aquinas and Aristotle

Now, it is worth noticing that Thomas Aquinas also stands in contact with another master mind that had pondered on the problems of life just 1500 years earlier; probably the greatest mind that pagan Greece produced, and one of the world’s greatest thinkers and investigators—Aristotle of Stagira. This great man, the teacher and friend of Alexander the Great had, like Sir Francis Bacon, taken all knowledge for his province, and his subtle and restless intellect sought to probe all the secrets of the mystery-laden universe around him.

Aristotle’s teaching reached St. Thomas in a mutilated and imperfect form, but the kindred soul recognised at once the pure gold of genuine thought; and so Thomas set himself to master all the secrets of Aristotle—sifted out all that was best in him, and incorporated it into the Catholic system. And the glorious synthesis he produced is enshrined for us in his immortal works, especially in the incomparable “Summa.”

Aristotle had no supernatural revelation to guide him, though some think he may have studied the sacred books of the Jews. He is the supreme example of pure reason working faithfully to reach the goal of truth. He is, therefore, in the true sense of the word, a Rationalist—and behold! his system is of all pagan philosophical systems the one that fits in best and most easily with Catholicism. Aristotle’s system has been to a large extent absorbed by the Catholic Church, and through the Church the terms used or invented by Aristotle have become current coin of our daily speech.

Now, why is it that Thomas Aquinas, whose great brain grasped the Catholic system in all its bearings as few other brains have ever grasped it, found in Aristotle so much that was in tune with Catholic doctrine? Why did St. Thomas find that Catholic Mysteries, such as the Trinity, the Incarnation, the Eucharist could be most easily set forth in terms of Aristotelian philosophy? Simply because the Catholic system is based on reason, appeals to reason, and the more faithful one is in following the pure light of reason, the more certain is he to arrive at, and find complete satisfaction in the all- embracing divine philosophy of the Catholic Faith.

The Church’s Line of Defenders

I have cited a few of the Church’s great line of defenders. One might expatiate endlessly on the innumerable other great intellects whose work in defence of Catholicism as a reasonable religion has been so splendid. They are a mighty band, and their testimony constitutes historical evidence of the first order in favour of Catholicism.

That is, they are capable witnesses, who have examined the question from every point of view, have weighed every objection, pondered every difficulty that the wit of man has ever brought against the Christian position. And their deliberate and reasoned verdict has been unhesitating acceptance of Catholicism as the only true solution of life’s problems.

Macaulay

Lord Macaulay, in his famous Essay on Von Ranke’s History of the Popes, discusses this argument. He feels the force of it. He admits that when a man like St. Thomas More, Chancellor under Henry VIII., “one of the choice specimens of human wisdom and virtue,” lived and died a fervent Catholic, and accepted all the Church’s doctrines, including the doctrine of the Real Presence—it is a staggering fact, not easily accounted for. And what is Macaulay’s explanation? For, of course, being a “Rationalistic” historian, he must find an explanation. Simply this: he calls it “superstition,” and adds that for the vagaries of superstition there is no accounting!

Think of the sublime impudence of it! Thomas Babington Macaulay, essayist and historian, sits in judgement on the saints and doctors of nineteen centuries of Christian thought—on Augustine and Jerome Aquinas and Duns Scotus, Anslem and More, and all the vast host of Catholic witnesses, and solemnly declares ex cathedra—and with evident consciousness that this is an infallible pronouncement—that all those thousands of men who spent their lives in scrutinizing Catholic doctrine, in conforming their lives to it in practice, were the victims of crass superstition, had been somehow or other deluded into accepting as the revealed Truth of God doctrines which, in reality, are mere fantastic absurdities!

Surely such an explanation is itself the greatest possible absurdity? Yet that is still today the attitude of modern “Rationalists” towards Catholicism. These men who deny all miracles are asking us to accept an explanation which itself would be a miracle of the most inconceivable kind. They ask us to believe that the whole of Christian civilization (which is the product of the Catholic Church) and all the beneficial results brought about by the teaching of Catholic doctrine— the abolition of slavery, the establishing of the sanctity of marriage and the dignity of woman, the purifying of morals, the sweeping away of the nameless vices and abominations of paganism—in fact all that goes to make up the glory of our civilized life, all that is founded on a lie, is the outcome of nothing better than degrading superstition!

PART II.

We have thus far considered briefly the number and character of the people who have been defenders of Catholicism. Let us now dwell for a few moments on another fact which stands out clearly in the history of our religion viz., the steadfastness with which it has clung to its principles and maintained unchanged its spiritual identity through nineteen centuries of incessant battling with hostile forces—opposing systems and organizations of the most formidable kind.

Experience shows that the tendency of human institutions is to change and finally decay. In the department of religious organizations perhaps, no period of the world’s history has seen such enormous and far reaching doctrinal changes in Christian sects outside the Catholic Church as the past fifty or sixty years.

Christian bodies that have hitherto clung to fundamental Christian ideas and principles, such as the Divinity of Christ, the inspiration of the Bible, the Virgin Birth, the Resurrection, have within the past half century become riddled with Modernism—that is, have relaxed their hold on some or all of these inherited Christian ideas.

A New Edition of the Bible

The party in the Church of England that one would have expected to be most tenacious of age-long Christian doctrines is the Anglo-Catholic or High Church party. Yet, in 1929 there was published in England by members of this branch of the Anglican Establishment a new Commentary of the whole Bible, comprising introductions to the various books and notes on the text. It is a work of vast research and scholarship; no less than fifty-three writers take part in it. Its general editor was the late Dr. Charles Gore, formerly Bishop of Oxford. It no longer regards the Bible as an inspired book. Of the introductory essay by Dr. Gore a competent critic writes: “Its purpose is to remove from the path of exegesis all such inspiration as connotes either Divine authority or inerrancy in the Scriptures of both Testaments alike.”

Four centuries ago the spiritual ancestors of these Anglicans cried out emphatically that the Bible is the only source and fountain-head of revelation in the world, and fiercely denounced the Church of Rome for holding that Christ left not merely a Book, but also a living, teaching Authority to interpret the Book, and that this was the only safe way of transmitting without error the deposit of Divine Faith from generation to generation for all time.

If it is so with High Church Anglicanism, it is, of course, far worse in the Non-conformist sections—they have practically thrown overboard all the great Christian doctrines. Yet, these sects have been in existence only a few centuries. Where will they he in another hundred years?

Now, the remarkable thing about Catholicism is that it does not change thus. For some unexplained reason—that is, unexplained by those who deny her divine origin and authority—she clings steadfastly to her doctrines and principles, no matter what pressure is brought to bear from without or from within, and in spite of the tendency to change and decay which is ingrained in every human institution.

When Catholicism was Born

The Catholic Church came into existence in the midst of one of the greatest material civilizations history has known. In the Graeco-Roman world around the Mediterranean, Athens supplied the culture, Rome the material comfort and strong government that made personal development and enjoyment of life possible.

Yet the new religion did not hide itself away in a corner; it invaded at once all the great cities; and it did so just because it claimed the allegiance of the Intellect of mankind—it appealed to Reason as being a complete and satisfying solution of all the problems of life.

It met, of course, with the opposition of sceptical minds—it had to face ridicule—it found its way barred by all the obstacles which strong, living, human passions always raise against those who aim at the higher good. Yet the new Faith swept like a flame from city to city; from Jerusalem to Caearea, Damascus, Antioch, through Galatia and Phrygia, to Roman Asia, through Philippi, Amphipolis, Thessalonica, to Athens and Corinth. Earlier still, the Faith had been preached in Rome—the great capital city. The leaven of Christ’s teaching had been flung into that huge cauldron where all the cults and all the vices of paganism were seething; and the leaven was already doing its transforming work.

Rulers of Destiny

Picture to yourself some haughty senator, in the days of Nero, pacing leisurely in his luxurious gardens on the Aventine Hill, and gazing across the Tiber at the huddled dwelling-places of the poor Jewish folk, situated in what is now called the Trastevere region. If anyone had told that senator that the future of civilization and of the world lay in the hands of a few beggarly foreigners, dwelling in the miserable tenements of that sordid Ghetto, what would he say? Yet so it was. Peter, the Jew, from Galilee, with a handful of fellow Catholics, had lately come to Rome and was delivering the message, laying down the principles, preaching the doctrines, propagating the Faith, which Catholics still hold; and which we hold just because, through the loyal fidelity of the Catholic Church in discharging her mission, the teaching of these Apostles of Christ has been handed down to us safe and sound across the gulf of ages.

Then, after a while the great pagan city became aware of the new force in its midst—it saw the danger and swooped down to destroy it. It seemed an easy task for the strength of mighty Rome. She had conquered the whole world; had crushed the empire of Alexander and annexed its fairest provinces; had stretched a strong arm across the sea and seized Jugurtha, the wily and dangerous Numidian King and shut him up safely in the Mamertine dungeon on the Capitol, and there let him starve to death. Surely it would be easy to destroy this new and insignificant Syrian sect. They would seize the chiefs of it—one, especially, whom his fellow Christians greatly honoured, a Jew named Peter, from Galilee—throw him, also, into, the Mamertine prison, where Jugurtha had perished; then, after a while, bring him forth—and, as an example to the world of the folly of resisting Caesar, crucify him on the Vatican Hill. Mark the place! the Vatican Hill. There Peter died for his Master. And just because of that far-off tragic event, the Vatican Hill is, today, the centre of the world’s spiritual life. A few authoritative words spoken from the Vatican Hill, by a man who has inherited the Faith and Authority of Peter, find a ready acceptance and willing obedience in every corner of the globe wherever Catholics are to be found. The pagan Empire that crucified Peter and strove to crush the doctrine he was preaching has vanished from the face of the earth, leaving hardly a trace behind. But the spiritual empire founded on Peter holds sway over wider realms than Imperial Rome ever dreamt of, and that empire is every day growing wider and stronger, and more firmly rooted in men’s souls.

New Foes

When the Catholic Church had gradually ousted the pagan gods, then other foes and other forces rose up to do battle against her. Within her own borders the fires of Arianism burst forth to test from within the strength of her doctrinal system, and blazed fiercely for many a long day.

Then, after a century or two, the storm of Mohammedanism burst upon her, and for a thousand years she was in almost incessant conflict with this strange Oriental cult, that sprang up as if by magic from the sands of Arabia and swept irresistibly across the world, almost engulfing Europe and turning it into a province of Islam. But, again, Catholicism and its principles prevailed, though it was not until after the victory at Lepanto, in 1571, and the rout of the Turks by Sobieski, in 1686, that the Christian world felt secure from the Mohammedan menace.

Then the thunder-clouds of the Protestant Reformation filled the sky and broke with terrible violence over Catholic Europe. The Church was shaken to her very foundations, she seemed to be losing her hold on men’s minds; yet she emerged triumphant from the struggle. Some fair provinces of her spiritual realm were torn from her, but she herself was marvelously purified and strengthened in the conflict.

After the Storm

And now it is four hundred years later. The Reformation tornado has passed; the forces evoked by Luther have spent their force, and Catholicism must gird itself to meet new enemies that are arming for the fray.

But the point I would direct attention to is how marvelously strong and vigorous and full of life this Catholic Church is after her stormy voyage across those momentous nineteen centuries! One would say that to her a century is as a year of life, and that only now is she approaching the hey-day of youth!

To illustrate this, think of the two doctrines that are most characteristic of Catholicism and that have been exposed to the fiercest attacks of her enemies—namely, the authority of the Pope and the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist; and see whether these doctrines play a less intense part in the life of the Church in the twentieth century than they did in past ages.

I think I am safe in saying that at no period of the Church’s history have these two factors of Catholicism—the Papacy and the Eucharist—been so strongly emphasized, so honourably recognized, so passionately clung to and defended as they are today.

A vivid and palpable proof of the part which faith in the Eucharist plays in Catholic life is furnished by the great International Eucharistic Congresses of the past forty years, held in capital cities all over the civilized world. The success of these Congresses surpassed the wildest dreams of those who suggested them. Never in the long history of the Church have there been—at least outside of Rome—such magnificent public demonstration of Catholic belief in the Real Presence of Christ. That same intense belief is also responsible for the extraordinary increase in daily Communion since the great Eucharistic decree of Pope Pius X. made frequent reception easy for all the faithful.

Then, too, the events of the past fifty years, especially the happenings during the Great War and the world wide recognition of the splendid work and influence of Pope Benedict XV., and of our present Holy Father, Pius XI.; furthermore, recent events connected with the restoration of the temporal power and the recognition of the fact that the Pope, as head of a vast spiritual organization, including in its ranks men of every nation under heaven, must himself be quite independent, owing allegiance to no temporal sovereign, in order that he may be an impartial ruler of all—these events emphasize the unique position accorded to the Pope even by non-Catholics the world over. When we add to this the deep and special reverence and submission shown to him by the three hundred millions of his own subjects, one may well ask: On what foundation does this extraordinary dignity of the Pope rest—this majesty and authority recognized in one man alone of the whole human race?

The answer is: On the Catholic doctrine of the Pope’s right to teach and rule as the successor of St. Peter. It is Catholicism that gives him his strength, and the honour paid by the whole world to the Papacy is a tribute to the unshakeable strength of the Catholic system, of which the Pope is the living embodiment.