The Catholic Church and Reason, Part 2*

By Rev. H A. Johnstone, S.J.

THE LOGICAL BASIS OF THE CATHOLIC FAITH

The Catholic who was asked about the foundation of his religious beliefs would refer first to the authority of the Church. Then if you asked him why He accepted the authority of the Church, he would tell you that he did so because it taught with authority from God. Asked how he knew that, he would say that the Church was founded by Jesus Christ to teach in His name, and Christ was God. Pressed further to give reasons for this, he would say that we learn from certain trustworthy historical records, which we call Gospels, both that Christ was God and that He established a Church to convey His teaching to the world, that He gave it authority in spiritual matters over all men, and that He promised to preserve it from error.

This is in outline the logical basis of the Catholic religion, which I wish to explain to you a little more fully, taking the steps in their natural order. Catholics give an important place in their scheme to faith; and faith means accepting information on the word of another. The faith of Catholics is divine faith, which means accepting truth on the word of God. This faith, which comes to us through the grace of God, is naturally very precious to us; and it is obviously a perfectly secure basis for religious belief, for whatever God teaches must be true. Our faith, however, is .far from being a blind faith. We do not accept authority until we have proved that the authority is real. We are not like those, for instance, who base their religion on the Bible and the Bible alone, without being able to give any very logical explanation of why they do so. Our faith supposes the exercise of reason going before.

THE EXISTENCE OF GOD.

We begin by proving the existence of God by sound and convincing arguments. By the use of our reason we can also find out much about the nature of God. The Catholic Church, which—as I showed in a previous talk—is always the steadfast defender of the rights and powers of the human intellect, maintains firmly that we can prove by reason alone the existence of God, and can, by the use of our reason, learn much about the nature of God. Reason shows us, too, our total dependence, as creatures, on God and our foremost duty in this world to honour, serve, and obey God.

We prove the existence of God and we learn what reason can teach us about the nature of God from the observation and study of ourselves and the world about us. God reveals Himself in the things which He has created. It is to be remembered that the know ledge thus gained is imperfect and incomplete, because creatures cannot give us an adequate knowledge of God, seeing that He is infinitely superior to them and essentially different from them. Even when we shall see God face to face we shall never be able to grasp more than a small portion of what there is to be known of God‟s greatness, power, goodness, and beauty, because our minds are finite, or limited, and God is infinite or unlimited. In this life God can, of course, if He wishes, reveal to us more about Himself than our unaided reason could discover; and He can make known more clearly and more fully what are His will and plans in our regard. If He does, we are, needless to say, bound to listen and obey. The only question is: has He done so? The Catholic maintains that He has done so, and that satisfactory evidence of this can be given.

GOD HAS SPOKEN.

The evidence that God has spoken to us is contained chiefly in the Gospels, which are four short accounts of the life and teaching of Jesus Christ. Taking these four documents merely as historical records and judging them accordingly, we find that the most critical examination shows that they were really written in the lifetime of the generation which saw the events which they describe. Rationalist critics who wished to assign, and for years did assign later dates to the composition of the Gospels, have been forced systematically to make retreat after retreat from the positions which they took up. „There is abundant proof that the Gospels were known and quoted from the first century on, and it cannot be denied that the Gospels are incomparably better attested than any other ancient historical records.

Having proved that the Gospels are the genuine products of the age to which they refer, we next have to prove that they arc trustworthy. They were written by men who were in a position to know the truth; but did they tell the truth? I can only say here that both the matter contained in the Gospels and the manner of telling and the confirming testimony of external sources of information, and the effect produced on contemporaries who were in a position to test the truth „of the narrative, all combine to give us complete assurance that in the Gospels we have truthful history. I am not now going into the proof of each step of our case; I am only setting forth in outline the logical basis of the Catholic faith, to show that it is logical and reasonable.

Next we have to consider what we can learn from these reliable historical documents which we call the Gospels. It is something very wonderful. We learn of a Man who was born of a virgin mother, and who proclaimed that He came en earth with a message from God to men. More than that, He claimed authority over all men because He was Himself God, one in nature with the Father and the Holy Spirit. And the proof was not merely in the divine character of His teaching, but in His wonderful works and in His resurrection from the dead, and in the marvellous way in which, contrary to all human expectation, the religion which He founded triumphed over the most powerful adversaries.

God the Son became Man in order to redeem mankind, to make satisfaction for sin, and to elevate mankind by be- stowing on men a special kinship with God, just as He in His one Person united both divine and human natures. His divine plan was to incorporate all men in Himself, thus forming one mysterious body of which He was the Head. He instituted special means of grace in order to help man‟s weakness and bring about and strengthen that supernatural union with God which was to be man‟s highest dignity. He brought to us, besides, a clearer and better knowledge of God, as well as of God‟s will in our regard.

THERE IS ONE TRUE CHURCH.

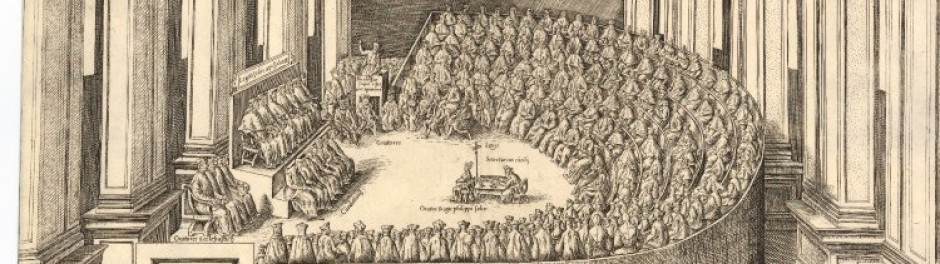

How was the plan of Christ to be made effective for the generations that were to come? This is the important question. Christ Himself did not live long. His public work was limited to a very short period, not much more than two or three years, and was confined to one small country. How were you and I to receive the benefits which Christ brought? Again we turn to the Gospels; and we learn that Jesus Christ established a body which He called His Church, and gave an order to the rulers of His Church to preach the good tidings to every creature and to the ends of the earth; that He gave authority to impose obligations in His name—“to bind and loose,” as the terminology was, and to hold the keys of the Kingdom of Heaven. This Church was to be for all ages; so Christ was careful to build it, as He said Himself, on a rock, so that the gates of hell—or the powers of death and evil—might never prevail against it. He promised, too, that He would be with His Church for all time till the world should come to an end, and that He would send the Spirit of Truth to abide with it for ever. Along with this commission to the rulers of the Church to teach and guide went, naturally, an obligation on all mankind to accept the teaching and obey the authority set up. “He that believes and is baptised will be saved; he that does not believe will be condemned.”

Immediately after the ascension of Christ into heaven and the descent of the Holy Spirit on the Apostles we find the Church in visible being. St. Peter and the other Apostles set about their work of teaching and governing, and their successors continued the work of conveying to the people for whom Christ died the means of sanctification which He ordained, and of giving the teaching and guidance which He had commissioned them to give in His name. Built on a rock, the Church of Christ could never fall, no matter what storms raged around it; and with the ever-abiding presence of the Spirit of Truth it could not err in delivering Christ‟s message. And so today the teaching of the Church which Christ established can be listened to with the same confidence as when the Apostles first went forth with their message. Christ is living in His Church, and when we listen to the Church it is to the voice of Christ Himself we are listening. “He that hears you hears Me, and He that despises you despises Me.”

FAITH AND REASON.

I think, therefore, you must admit that the basis of the Catholic religion is a logical one. The Catholic Church, and—I may add—Catholic Church alone, preserves a right balance between reason and authority, taking a sane course between unlicensed liberty of opinion, which produces such sad results, and blind adherence to a theory, which cannot withstand serious attack from the forces of unbelief. The Catholic Church wants us to use our reason. There is much we have to prove by reason before we can accept the authority of the Church, and the Church herself encourages us to understand her doctrines and the proofs on which they rest as well as we can. We prove by reason the genuineness of the Gospels and their veracity. From them we prove the divinity of Christ and the purpose for which He came on earth. From them we learn, that He did not leave it to every individual throughout the course of history to interpret for himself the meaning and application of His life and teaching. He took the practical means—the necessary means as would appear—of founding a teaching body to which He gave His own authority, promising it stability and freedom from error when it spoke authoritatively in His name, because on its permanence and truthful teaching would depend the salvation of all future generations. So, once I am sure that the Church teaches authoritatively certain doctrine as of divine origin, I owe the same submission to the authority of the Church as I owe to Christ Himself; and in my submission to her authority I have the assurance that the Church which He founded to guide me can no more lead me astray than could Jesus Christ Himself.

A GREAT GIFT.

What a consolation it is to know that the infallible and imperishable Church which Christ established exists today and must exist through all ages, and that through her we are as closely in touch with Him as were those who heard Him speak. From her we receive those supernatural helps which our human weakness so badly needs. By her we are led securely amid the storms which passion raises, amid the darkness with which our human intellects must often be surrounded, through a laud in which we live as exiles, to an eternal home. It is the duty of every man to be a member of Christ‟s Church; for us who have received, through no merit of our own, but through the grace of God alone, the gift of the true Faith, it is our most precious privilege.

CATHOLIC DOCTRINES ARE REASONABLE

In my last talk I explained the logical basis of the Catholic religion, and showed that when the Catholic Church teaches any doctrines authoritatively we are acting in a perfectly reasonable manner when we accept that doctrine as true, because Jesus Christ, who was God, established the Church to teach in His name, and guaranteed it against error in doing so. It is not strictly necessary to go any further than that in order to establish the reasonableness of our position. However, it may be well to make clear that though Catholics regard the authority of the Church as the chief and sufficient ground for their faith, they do not by any means exclude other motives and arguments. It is not to be thought that Catholics are expected to shut their eyes and open their mouths and take whatever doctrines are given them. I have already said that the Church is anxious that we should study and understand the doctrines of our religion and the arguments on which they rest. Just as an example, I will take one doctrine, and that not an easy one, and show that in itself it is reasonable, because it is supported by sound and reasonable arguments.

We Catholics believe that at the words of consecration in the Mass, pronounced by a validly ordained priest, that which was bread and wine becomes, through the power of God, the body and blood of Jesus Christ. We believe, con- sequently, that Jesus Christ is as truly present in the Blessed Eucharist as He is in heaven or as He was when He walked on earth. Why do we believe this?

THE BLESSED EUCHARIST.

We have four accounts of the institution of the Blessed Eucharist, three in the Gospels and one in St. Paul, and all are in substantial agreement. We learn that at His Last Supper, one of the most solemn moments of His life, Jesus took bread and wine, blessed them, and gave to His Apostles, with the words: “This is My Body; this is My Blood. Do this in memory of Me.” I know that some have said that Jesus Christ was on this occasion speaking figuratively, and I cannot stop to argue the point, for I am not now primarily proving that our doctrine is certainly true, but that it is a reasonable one, based on arguments that merit serious consideration. When the Son of God said, “This which I am giving you is the flesh which is offered for you and the blood which is poured out for you,” surely it is not unreasonable—to say the least—to take the words in their obvious literal meaning if there is no compelling reason to the contrary. I mention in passing that those who refuse to take them in their literal sense cannot agree in what precise sense to take them.

THE PROMISE.

I could, however, understand a person being held back by the thought of the tremendous import of the doctrine. It might seem almost too good to be true. Is there anything elsewhere in the life and teaching of Christ that would prepare us for such an astounding declaration? Just a year before He had been speaking in the synagogue of Capharnaum, and had promised a better food than the manna with which the Israelites had been fed in the desert. “The bread that I will give is My flesh,” He said. This extraordinary statement drew forth immediate opposition:

“How can this man give us his flesh to eat?” Did Jesus withdraw or moderate what He had said? No, He repeated it even more plainly and forcibly: “In very truth I say to you, except you eat the flesh of the Son of Man and drink His blood you will not have life in you.” Many, even of His disciples, we are told, said: “This saying is hard; who can accept it?”, and they went away and left Him, never to return. They understood His words literally, and He did not correct them; He let them go. Just one question—supposing He had wished to teach the doctrine of His real presence in the Blessed Eucharist, could He have done so more clearly and more emphatically? With this scene and these words in our minds are we not better prepared to understand what Christ said a year later at the Last Supper, “„Take and eat of this, for this is my body?”

What Our Lord said at Capharnaum was indeed hard doctrine for those who had never dreamt of such a thing. But we must remember that only the day before they had seen Him feed five thousand men, and women and children in addition, with five loaves and two fishes. After such a manifestation of divine power there was less excuse for those who abandoned Christ because they found His doctrine hard to accept.

TESTIMONY OF THE FIRST CENTURIES.

I could still have sympathy with the man who would say: “The words, indeed, in themselves seem clean But, also,

it seems too wonderful that under the appearance of bread or wine I am given the body, blood, soul and divinity of the Redeemer of the world. I should not dare to take this meaning out of the words, plain as they appear to be, on my own responsibility. I should like some further support. How, for instance, did the early Church receive and interpret these words?” The question is a reasonable one, and is easily answered.

There is, naturally, not a great deal of Christian literature surviving from the, early days of the Church, but there is enough for our purpose. St. Paul, who belonged to the first generation of Christians, writes: “Whoever eats this bread and drinks this cup unworthily is responsible for the Body and Blood of the Lord,” that is, is guilty of an offence against the Body and Blood of the Lord. (I Cor. xi., 28). St. Ignatius the Martyr, who died less than a century after Our Lord, wrote concerning a sect called the Docetae, who denied the reality of Our Lord‟s human body: “They abstain from the Eucharist because they do not confess that the Eucharist is the flesh of our Saviour, Jesus Christ, that suffered for us.” (Ep. ad Smyrn, 8). St. Justin Martyr, who died about fifty years later (in, 167), is equally explicit: “We have been taught that the food consecrated by the word of prayer coming from Jesus Christ . . . is the Flesh and Blood of that Jesus Christ who was made Flesh.” (Apol. I., 66). Go on some twenty years further to the great Irenaeus, who was the disciple of those who had known the Apostles. He writes:

“Wine and bread are, by the word of God, changed into the Eucharist which is the Body and Blood of Christ.”

(Adv. Haer. V. 2. 2)-. I could go on and give even more striking quotations from St. Hippolytus, in the early part of the third century, from. St. Gregory of Nyssa and St. Cyril of Jerusalem in the fourth century. And the same doctrine is proclaimed with equal clearness and emphasis by St. John Chrysostom, St. Cyril of Alexandria, St. Hilary, St. Ambrose, St. Augustine, and all the great Fathers of the Church. Therefore, in taking the words of Scripture according to their plain meaning, I am in good company.

LATER HISTORY.

For century after century the doctrine of the Real Presence remained—beyond all dispute—the centre of the faith and worship of the Church. Even the Nestorians and Monophysites, heretics who broke away from Rome in the fifth century, and the Greeks, whose schism began in the ninth century, receiving no influence from Rome afterwards, retained and still retain their belief in the Real Presence. The first falling away of any consequence came in the sixteenth century with the Lutherans, Calvinists, and Zwinglians. Luther could not at first bring himself to deny the doctrine, though he would have liked to do so, because, as he said, “I saw that in that way I should have been able to give Popery the greatest slap in the face.” “I cannot get over it,” he said, “the text is too powerful; no words can change its meaning.” And he poured ridicule on the views of Calvin, Zwingli, and others. He himself, however, soon fell into error on this point as on so many others, and his views became confused and contradictory.

But while the rejection of authority and the principle of private judgment opened the way to every variety and confusion of opinion, the unchanging Church which Christ established never wavered in maintaining the doctrine of the Real Presence which it had held from the beginning.

As I have already said, I am not now engaged expressly in proving the truth of this doctrine. I am showing only that the doctrine is a reasonable one, because based on arguments which would command the respect of any reasonable man. Of course, if you insist on taking the words of Holy Scripture in a sense other than their natural one; if you can disregard the belief of the early Church; if you decide to attribute no weight to the teaching of the Fathers; if you make up your mind to go counter to the unbroken tradition of centuries; if you are able to suppose that the Church which Christ promised would have the guidance of the Spirit of Truth; erred about a doctrine of primary importance throughout the whole of her history—if you can do all this, I admit, then, that you can deny the doctrine of the Real Presence of Jesus Christ in the Blessed Eucharist. But would you say that such a position was reasonable? Bold, startling, revolutionary, if you like. But reasonable? On the other hand, I think I am not extravagant in claiming, as a result of the arguments which I have put before you, that the belief of Catholics is a reasonable one. And that, I may remind you, is what I set out to show in this series of talks—that the Catholic religion is base a on reason.

DIFFICULTIES.

But are there not great difficulties concerning this doctrine which we are discussing? Oh, certainly; because God can do many things that I cannot understand. I do not however, refuse to believe on that account. Do I understand the mystery of the Incarnation itself, of which The Blessed Eucharist is a development? Can I understand the miracle of the feeding of the five thousand? Even in the natural order, can I understand why a planet hundreds of millions of miles away from the sun is kept on its course round the sun? I can utter the word gravitation; but can I give any real explanation? Analyse common salt, and you will find nothing at all in it except sodium and chlorine. Sodium is a metal which ignites when thrown in water; and chlorine is a poisonous gas. Can I understand how, when these substances are chemically combined, they form a palatable and useful addition to our food? I am not surprised if there are difficulties for my human intellect in any of God‟s works. It requires a good deal of knowledge and study to understand even and formulate the difficulties which are to be found in the doctrine of the Real Presence, and I think we have a right to demand that those who raise objections should know what they are talking about. A certain dignitary said in the course of controversy last year concerning the Eucharistic Congress that it was absurd to suppose that God could be confined within the limits of a host. He believes that Christ is God. Does he suppose that the Godhead is “confined” within the human nature of Christ? The plea of knowing no philosophy or theology is no excuse for talking sheer nonsense about Catholic doctrines.

COMMON SENSE AND GOOD WILL

I have often thought it strange, though significant, that the Catholic doctrine of the Blessed Eucharist can excite such bitter opposition. The fact that we can sincerely, devoutly, and—as I have shown—not unreasonably, believe that in the Blessed Eucharist Jesus Christ is as truly present with us as when He lay in the manger at Bethlehem or taught at Capharnaum, or hung on the Cross; and that we receive Him really, under the appearance of bread, as the food of our souls, should, it appears to me, excite envy rather than attack. Would you not wish to be able to believe a doctrine which can bring so much consolation and spiritual strength? “By the fruits the tree is known.” If I could let those of you who are not Catholics see, not merely external results like our thronged churches, but the heartfelt devotion to Jesus Christ that springs from, our doctrine of the Blessed Eucharist, I think that you could not fail to have more sympathy with the doctrine. If I could make manifest to you the purity and holiness of life that are fostered among the young people in our boarding schools by the practice of daily Communion and by the intimacy with our Lord which results from frequent visits to the Blessed Sacrament, and leave you to compare this with what is likely to happen—and so commonly happens—when such helps are absent. I do not think that any good man or woman would ever say a word against our doctrine, even though he or she personally was not able to believe it.

I have taken this doctrine, as I have said, only as an example. What I want to make clear is that the Catholic Faith is reasonable, not only because the Catholic position as a whole is a logical one, having as its main foundation the divine authority given to the Catholic Church by its Founder, but also because every, single individual Catholic doctrine has a reasonable explanation and defence.

LOOK ON THIS PICTURE AND ON THAT

If a religion is to claim, the serious attention of men it must have a reasonable foundation. It is because the Catholic religion is based on reason and appeals to reason that you are asked to take an interest in it. In my last two talks I was engaged in showing that the Catholic religion, both as a system and in its several parts, really is based on reason. I wish now to strengthen the claim of the Catholic Church in this respect by showing that not only does she possess this characteristic, but that she possesses it exclusively. No other form of religious belief has a logical foundation.

I will try, in what I have to say, to avoid all matter of dispute and refer only to acknowledged facts. The facts will, I think, make clear that whatever may be said in favour of other forms of religion—and I have not the slightest desire to attack them—they cannot appeal to logic for their support. And I give a plain reason for what I say. A logical system must be consistent; it cannot contain contradictions. A logical system must recognise a difference between “Yes” and “No,” and must not answer “Yes” and “No” to the same question. A logical system must move to definite conclusions by an intelligible process of reasoning. Restricting myself to this one point, without going into troublesome questions of history and problems of origins or taking up any particular doctrines in detail, I will show that non-Catholic religious systems— as opposed to the Catholic religion—are illogical because they are inconsistent; they cannot be based on reason because they are full of contradictions. Seen against this background the logical character of Catholicism will stand out all the more clearly.

HARMONY OR DISCORD.

At a Summer School for Anglican clergy in England as late as July last, (1935) one of the speakers, after quoting St. Paul, “If the trumpet give an uncertain sound who shall prepare himself for the battle?” went on to say: “For the last four hundred years there has been a measure of uncertainty as to what tune the Anglican trumpet is going to choose for its clarion call.” The period mentioned, I may interpolate, is the whole lifetime of Anglicanism. “At the moment,” the speaker continued, “the Anglican orchestra is playing four distinct tunes—Catholic, Moderate, Anglican, Modernist, and Evangelical. It is sometimes maintained that the combination results in the achievement of a gorgeous polyphonic melody…. . But it is foolish to deceive ourselves into thinking that this is the impression which the general public is receiving. The world today hears not harmony but discord. In its ears the sound of the Anglican trumpet resembles the painstaking efforts of a brigade of Boy Scout buglers. There is much expenditure of breath, and a brave display of individual effort; but there is no agreement among the performers either as to the tune or as to the time, and there is an unfortunate lack of conviction about the high notes.” I have been quoting, let me remind you, an Anglican clergyman* addressing a number of other Anglican clergymen not many months ago. The only comment I make is that four tunes would appear to be an understatement. I should think it a more accurate comparison to say that the orchestra was playing the works of four different composers— suppose Bach, Beethoven, Mendelssohn, and Stravinsky— and every player was choosing the work of these composers which he liked best.

Is this an exaggeration? I open an Anglican Church paper and look at the advertisements offering positions to clergymen. Here are some of the types sought for: “Catholic,” „„Anglo-Catholic,” „„sound Catholic,‟‟ „fully Catholic,” „„simple Catholic,” „„thorough Catholic,” „„sensible Prayer Book Catholic,” “sane Catholic,” “Evangelical Catholic,” “liberal Catholic,” “Catholic-minded,” „„Catholic without being extreme,” “the whole faith,” “no extremes,” “moderate views,” “not moderate,” “Evangelical,” “liberal Evangelical.” “definite Churchman,” “sound Churchman,” “Moderate Churchman,” “very moderate Churchman,” “central Churchman,” “broad Churchman,” “Churchman, but with flexibility,” “open-minded.” And remember these are all taken from one particular paper, the organ of one particular party, where you would expect some kind of uniformity. What would the result be if I quoted from a variety of papers?

THE POINTS OF DIFFERENCE.

But it might he thought that the diversities and inconsistencies are concerned with matters of slight importance. On the contrary, all the main doctrines of Christianity are in question. The divinity of Christ is the central point of Christianity, and there is not agreement even about that. The birth of Jesus Christ of a virgin mother and His resurrection from the dead are accepted by some Anglicans as plain facts; for others they are fables. To some the Scriptures are the word of God, and therefore free from error; to others they are human documents of varying value. Some recite the Athanasian Creed and believe it; others recite it and do not believe it; others refuse to recite it. One small section will grant a primacy “„by right divine” to the Pope; the most fervent prayer of others is one which it might be unbecoming to quote here. Some hold the Catholic doctrine of sacraments and sacramental grace; to others this is “magic.” Some urge the practice of sacramental confession; to others this is a symbol of all that is wicked. The doctrine of eternal punishment is certainly true for some, certainly false for others. In some Anglican churches we have so-called “Mass”; those who stick to the Thirty-nine Articles regard Masses as “blasphemous fables and dangerous deceits.” Some Anglicans believe in the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, and believe He is to be adored there; others regard this as idolatry. Some offer prayers for the dead; others look on this as superstition. Some regard the doctrines of the Established Church of England as no matter for parliamentary decision; the late Archbishop Davidson of Canterbury, said, “I dissent altogether from that view and dissociate myself from those statements.” Some regard the Reformation as the greatest blessing England ever received; others cannot find words strong enough to express their detestation of it. Many allow remarriage after divorce; others hold this to be sinful. Many side with Catholics to uphold the purity of married life, a majority of more than three to one of Anglican bishops gave approval to what we hold to be, and hold can be proved to be, unnatural vice. What one bishop teaches another denies. I once took up an Anglican Church paper to find a letter from the retired predecessor of a diocesan bishop in which I read: “I must be forgiven if I definitely state that I do not believe the Church of England authorizes the Church teaching put forward by my successor.”

THE FACT ADMITTED

Did time allow I could give chapter and verse to illuminate all these views and many shades of opinion in between. I could, for example, instance a recent edition of the Gospel of St. Luke, brought out by an Anglican clergyman under the general editorship of an Emeritus Professor of Divinity at the University of Cambridge, which openly scoffs at the miraculous and the supernatural in the Gospel, quotes a non-Christian as its most approved authority, denies the truth of large portions of the narrative, and apologises for using capital letters in pronouns referring to Jesus Christ. And the instructions of the general editor to the particular editor of this text were:

“My idea of your book is that you could write as though you had your boys before you and were actually teaching.” The seriousness of the situation is recognised by the Anglicans themselves. The quotation which I gave early in this talk is not unique. As long ago as 1913 Bishop Gore wrote to The Times (London): “I do seriously think that, unless the great body of the Anglican Church can again speedily arrive at some statement of principle such as will avail to pull it together again in a unity comprehensive but intelligible . . . it will go the way to certain disruption.” And the position has by no means improved since then. “For the moment,” wrote the Church Times a few years ago, “we must accept the fact of the comprehensiveness of the Church of England, even though we may believe that Catholicism and Protestantism are mutually contradictory and mutually destructive.” Bishop Knox, an uncompromising Protestant, wrote „in 1928: “For nearly half a century there have been within the Church of England teachers and followers of what are fundamentally two distinct religions. This situation has been recognised as scandalous by all who believe that a Church ought to teach consistent truth in all matters essential to salvation.”

AUTHORITY LACKING.

It is much the same in other denominations. I had occasion once before to quote the reply of the Methodist Times (London) to the charges that Methodism was abandoning the old, sound Christian beliefs that had been its strength. They were proud of it, because “a living Church must change.” Within the last few months a distinguished young Methodist minister in England, Mr. T. S. Gregory, entered the Catholic Church. In the course of a letter to the Methodist Times (which, by the way, is edited by his cousin), he writes: “I heard responsible members of the Church openly doubt the deity of Christ, the resurrection of the dead, and the life of the world to come; and when I asked what authority decided how much of the Christian faith a Methodist must believe, I was told by a distinguished and saintly leader of Methodist thought that Methodism had no dogmatic authority.” We have heard ourselves an Australian Presbyterian, in a position of authority as a teacher, deny the divinity of Christ, and practically every important distinctively Christian doctrine; and there was no agreement among his fellow Presbyterians whether he was right or wrong, whether he was to be tolerated or not.

THE ABANDONMENT OF REASON.

Many nowadays give up the struggle and abandon all definite doctrine, making of religion a kind of jelly-ash. How often do we hear from writers who have more fluency of pen than power of logical thought, that Christianity is not a system of dogma, but a way of life.” But this is only going still further along the road of absurdity. Of what use is sentiment if there is no fact behind it? Why be loyal to Jesus Christ if we do not know who He was or what was His authority? “Christ did not teach any doctrines,” we are told. What nonsense! Christ taught and proved that He was God. He taught the mystery of the Blessed Trinity. He taught that He came down from heaven to give Himself for the remission of sin. He taught the necessity of baptism. He taught the doctrine of eternal punishment. He taught the indissolubility of marriage. He said that the bread which He would give was His flesh. He taught the doctrine of eternal life with God. He taught the obligation of listening to the Church which He founded. The dogma of “no dogma at all” is a counsel of despair and the surrender of all pretence of reason.

I know there are many good and earnest people outside the Catholic Church who love Jesus Christ and hate what is evil. But they are in an illogical position. Christ gave to His Church authority to teach; it is illogical for a follower of Christ to be where there is obviously no teaching authority. Christ told the rulers of His Church to teach men to observe all that He had commanded; it is illogical to suppose that this commission is being carried out where men can believe just what they fancy. Christ said that the Spirit of Truth would be with His Church for ever; it is illogical, and worse, to suppose that the Spirit of Truth is dwelling where contradictions are taught and believed. “ Look on this picture and on that.” On the one hand you have the Catholic Church, with a clear and logical position, possessing authority and exercising it, teaching the same doctrine consistently in all places and at all times. On the other hand you have inconsistency, contradiction, and absence of authority. On which side does reason lie! I can safely leave you to give the answer for yourselves.

A PRACTICAL TEST

I have been speaking on the subject of the Catholic Church and reason because we are, on the whole, reasonable beings; and, especially in an important matter like religion, „men want sound thinking. It is true that our lives are not ruled altogether by reason. Early associations and training, habits of thought acquired in a haphazard way, family and personal influences, and—unfortunately—prejudice and self-interest, prevent reason from being the sole determining factor in our lives. But still, reason plays an important part. Hence, if we could put a reasonable case before people who were sufficiently interested and sufficiently unbiased, we should expect that it would win the acceptance of a considerable number.

Now if what I have been saying about the Catholic Church is true; if in reality the Catholic Church has a reasonable ease to present, I should expect this to have manifest results. In spite of the obvious difficulties that there are in putting the Catholic ease before those who are outside the Catholic Church (difficulties with which I dealt early in this series of talks), I should expect to find a steady influence exerted by the Catholic Faith, drawing men to accept it. Does this happen? I answer that it has happened, and that it continues to happen. Every year not only men and women of no religious affiliation at all, but members of every denomination, in considerable numbers enter the Catholic Church. Statistics for Australia on this point are not recorded. But in England about 12,900 persons are received into the Catholic Church each year, and in the United States the number is over 40,000. This is a fact the significance of which is very commonly overlooked. I venture to think that most non-Catholics who are listening to me have never considered the importance of this fact, even if they have been aware of it.

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE FACT.

Let us look squarely at it. Every year thousands of men and women of every class of society and of every variety of religious belief conscientiously think it their duty, after very complete investigation, to become members of the Catholic Church while there is no such corresponding movement from the Catholic Church to other bodies. Here is a fact, and—like every fact—it must have a rational explanation.

Before looking for explanations, let us examine the fact a little more closely. It is true that Catholics, for various reasons, at times give up the practice of their religion. The Catholic Church is not a mere Friendly or Benefit Society. She imposes strict obligations on her members, and fidelity to her teaching demands a large measure of self-sacrifice, and often real heroism. Catholics, because human, can grow careless and negligent and fall away. We often are concerned with the problem of this leakage. But you do not find respected and conscientious Catholics becoming good Anglicans or Presbyterians or Methodists or Baptists, whereas you do find conscientious and respected members of every denomination coming into the Catholic Church. Anyone can think immediately of a list of names like those of Father Martindale, Monsignor Ronald Knox, Dr. Orchard, G. K. Chesterton, Arnold Lunn, and a dozen others. No one could think of a single name, equally respected, of one who for conscientious reasons left the Catholic Church to find a spiritual home elsewhere. It is not a remark I would make myself, but perhaps I may quote the saying of Lord John Russell, when someone offered him as consolation the fact that people passed from Rome to the Church of England as well as the other way: “That is all very well; but while the Church of England loses some of its fairest flowers to Rome, we get in return only the weeds that the Pope throws over his garden wall.”

We now take this state of affairs for granted; but there must be some reason for it. The fact which I am discussing becomes more striking when we consider the great variety of classes represented among those who make their submission to Rome. There are among them, of course, a great number of humble folk, who are very dear to God, but will never make a name for themselves in this world. On the other hand, lists could be given of hundreds of people of high rank and title in England who have entered the Catholic Church. There is a constant stream of clergymen coming over; and they should be in a position to know what they are doing. Monsignor Robert Hugh Benson was a son of an Archbishop of Canterbury, for example; and Monsignor Ronald Knox is the son of an Anglican Bishop of the extreme Protestant school. This reminds me of a passage in the memoirs of another English Protestant Bishop (Forty Years On, by Bishop Welldon). He is very critical of bishops‟ wives, and sets out the advantages of celibacy for the clergy, ending with the argument that “unmarried clergy do not beget sons „who go over to the Church of Rome.” Among those who became Catholics are university professors, men of science, and distinguished writers—men who are not likely to act rashly, or without having made a close study of the step they are taking. There are members of every profession and walk of life. This year I can recall off-hand, among other cases, a vice-admiral of the Mediterranean fleet and a Dutch Cabinet Minister. Some are quite young, at school or university; others are men of mature years and experience. When the distinguished judge, Lord Brampton (better known as Sir Henry Hawkins) became a Catholic in his old age, lie said, “At least it cannot be put down to the impetuosity of youth.”

THE QUESTION OF MOTIVE.

An important point to remember is that every single one of the thousands who enter the Catholic Church every year must first receive a complete course of instruction in Catholic doctrine, and must understand clearly the basis of the claims of the Catholic Church. Further, they cannot be received into the Catholic Church simply because they are willing to be Catholics or consider the Catholic religion to be as good as any other, or even better than others. They must be convinced in their hearts that Jesus Christ founded one Church, and that Church the Catholic Church, and that it is strictly obligatory on everyone to become a member of it. We want people to become Catholics, but not on any terms. It would be wrong for me or any other Catholic priest to receive anyone into the Catholic Church who was not genuinely and sincerely convinced that the Catholic Church had authority from God and was the only true Church. That it is which gives its force to this argument drawn from all these converts. Every one of them must have real conviction.

It is true that non-Catholics are sometimes led to inquire into the claims of the Catholic Church through human motives. But they cannot enter the Catholic Church for any merely human motive. I had the experience once of a young fellow who came to me for instruction in the Catholic religion chiefly because his intended wife—a staunch Catholic—~insisted. After we had gone a certain distance in our study I said to him one day. “Now, Jack (this not being his name), you understand the Catholic position fairly well. What do you think of it all?” “Well;” said, Jack, “of course I came in the first case because of Mary (this, again, not being her name); but even if we separated now I would have to go on with it.” You may begin to inquire for various reasons—mere curiosity, for instance; but you can become a Catholic only for one motive—because you sincerely believe that the Catholic Church is the one true Church, and that it is your duty to be a member of it.

It is well worth noticing, too, that a large number of those who enter the Catholic Church have to make sacrifices to do so. Natural motives are, more often than not, altogether against the step. It means braving public opinion in many cases and conquering human respect. More: it means sometimes estrangement from friends. Families will—it seems hard to believe—sometimes disown those who follow their conscience and enter the Catholic Church. Even means of livelihood have sometimes to be sacrificed by those whom God calls to the Catholic Church.

And so I repeat, here is a fact of the greatest significance: every year thousands of upright and honourable men and women of every shade of belief, after much study and prayer, make their submission to the authority of the Catholic Church, though the step involves often great sacrifices, and then find in the Catholic Church all that they expected and more. On the other hand you will not find good and earnest Catholics leaving their Mother to seek elsewhere the spiritual nourishment which she has been unable to provide. Not only does this not happen, but it is a thing no one expects to happen.

WHAT IS THE EXPLANATION?

A fact like that needs a rational explanation. What explanation can you give, but the one which I suggested at the outset, that the Catholic Church has reason and truth on her side? If I knew of any other reasonable explanation I would put it forward and discuss it. But I know of no possible explanation, nor, with years of experience as professor of philosophy in putting objections and difficulties to students, can I even imagine any plausible explanation but one. That is why I put forward the fact of this steady stream of earnest converts as a very strong confirmation of what I have been maintaining here for some weeks, that the Catholic Church has a reasonable case, which when examined seriously and without prejudice, must commend itself to the human mind.

I have come to the end. I began this series of talks by analysing the causes of the neglect of religion today outside the Catholic Church, and showing that the Catholic Church alone could offer what men wanted. In a preliminary outline I proved that the Catholic Church was the true defender of reason and took her stand on reason. I then pointed out that she, was not always met by her opponents on the ground of reason, and that logic was not wanted by many of those who were hostile to the Catholic Church. Even in the case of the ordinary man I showed the real danger of being blinded by prejudice and the harm that might result. I put before you the logic of the Catholic position as a whole, and gave, you the example of the reasonableness of individual Catholic doctrines. I drew a picture of the confusion and contradiction that reign outside The Catholic Church. Finally, I have now suggested a test of the reasonableness of the Catholic case, the results of which must impress anyone who gives them consideration.

AND NOW THE PRACTICAL APPLICATION

I have always assumed that, in so far as I was speaking to non-Catholics, I was speaking to people of good-will who were anxious to do what was right. Let us put this good-will to the test. If you were convinced that the Catholic Church was established by Jesus Christ and that it was His will that you should be a member of it, would you become a Catholic? Even if there were difficulties in any way—danger of the alienation of friends, or of loss of position and consequent suffering for wife and children, would you face this if you knew it was God‟s will? Further, if it were shown that the Catholic Church had at least a reasonable case, and was in fact the only Church that really appealed to reason and could give a reasoned statement of its position, would you believe it to be your duty to examine that claim seriously?

Surely I have proved that much, at least. What are you going to do about it?

I ask Catholics who are listening to me to pray for their non-Catholic brethren. I ask those of you who are non- Catholics to get out of the groove along which you have been going, to lay aside opinions that you have held without examination and without logical basis, and give earnest, unprejudiced consideration to the claims of the Catholic Church. I beg of you even more earnestly to ask God for light and grace. Neither my talking nor your own investigations can give you, by themselves, the true Faith. Intellectual conviction is not enough. Faith is a gift of God.

Remember that it is no party spirit that I make these requests. I am moved only by what I believe to be the will of Jesus Christ, the Redeemer of mankind, and by regard for your own best interests. Through the Catholic Faith you would be able to know more surely God‟s will, and would get powerful help in the often difficult task of doing God‟s will. You would in the Catholic Church obtain more easily forgiveness of sin; you would have sure guidance in many problems that sorely perplex mankind; you would have a fuller knowledge of God‟s revelation to men, and a closer intimacy with Jesus Christ; you would be on a safer path to eternal life. On this account it would be the greatest calamity for any one of you if prejudice, or timidity, or indifference prevented you from making a thorough and, sympathetic investigation of the claims of the Catholic Church.

*Rev. Humphry Beevor in The Church Times, August 2nd, 1936.

Nihil Obstat RECCAREDUS FLEMING.

Censor Theol. Deput. Imprimi Potest

EDUARDUS, Archiep. Dublinen., Hiberniae Primas.

Dublini, die 22 Mai, anno. 1936