The Masterminds of Vatican II Part I: The Master Plan; Role of Freemasonry Fr. Francisco Radecki, CMRI

The Second Vatican Council, better known as Vatican II, was one of the most traumatic events in history. This council laid the groundwork for the creation of a radically new church during a four-year period from 1962 to 1965 by means of 12 monthly sessions. Its effects are still felt worldwide 50 years later.

How could anyone in modern times create a New Church that resembles the Catholic Church in externals, but is radically different in essentials? Who could have orchestrated and carefully implemented such sweeping changes worldwide?

The Real Mastermind Behind Vatican II

Although historians point to many of the masterminds who helped form this humanist religion and propagate its ideas, there was ultimately only one mastermind behind it all: someone with superior intelligence, power and influence, whose word was law and whose willing subjects followed his every command, who could offer unparalleled fame and even a cardinal’s hat or papal throne to those who did his bidding.

This individual is not a world ruler, although he wields tremendous influence over it. He is not a wealthy potentate, although he offers the world to all who heed his call. He is Lucifer, Prince of Darkness, whose one aim is to destroy God’s work and to lead as many souls as possible to the eternal fires of Hell. He is the mastermind of Vatican II. Lucifer created the Modern Church.

The changes that were made subsequent to Vatican II were set in motion centuries earlier by means of gradual infiltration and indoctrination, creating a mindset where “anything goes.” The documents of Vatican II became a manual with specific directions on how to create a new church.

The Modern Church replaced faith with reason, confidence in God with hope in humanity, Christian charity with philanthropy, the supernatural with the natural, grace with emotion, prayer with action, and God with the world. The word “Catholic” was retained in order to carefully veil erroneous beliefs and to prevent people from recognizing its diabolical origins.

How It Occurred

Over 250 years of groundwork prepared the soil for those who would ultimately become the architects, the masterminds of Vatican II. These men pertinaciously labored daily, following Lucifer’s lead, in order to destroy faith and sow the seeds of doubt. One cannot adequately understand what occurred at this council until you realize how the cardinals, bishops and theologians (periti) gained their positions of power, allowing them to ultimately control the Council. The long, tedious process took generations until, finally, all the ducks were in place.

Promises of power and fame were used to entice clergy to enter the ranks of those in secret societies in order to prepare the world for changes that would shake its very foundation. Since law enforcement officers and government officials can turn rogue and defy laws they have sworn to uphold, one should not think bishops and priests are exempt.

Freemasonry played a major role in preparing the world, clergy and the general populace for accepting and embracing the changes of Vatican II. Since these organizations are clandestine by nature, it is easier to obtain classified CIA secrets than those of influential lodges whose members take blood oaths.

Freemasonry

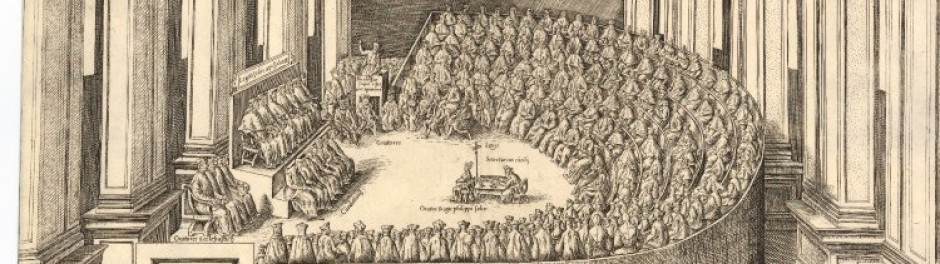

Freemasonry was founded in 1717 with the formation of the Great Lodge of London. Soon afterwards, Freemasonic lodges were established in Mons, Belgium, in 1721, Paris, France in 1725 and in North America in 1728. Freemasonry attempts to practically ignore the existence of God by disregarding His laws, removing inhibitions and offering unbridled liberty.

It was an ingenious plan. Masonic lodges had their origin in the guilds of brick-masons who built cathedrals. They used secret passwords in order to preserve trade secrets. Therefore, since few churches were constructed after the Reformation, lodges could be used for other purposes.

Adam Weishaupt, a former Jesuit and canon law professor, founded a secret society called the Illuminati in 1776 that aimed at creating a new world order that would ultimately destroy the Catholic Church and establish a humanistic world devoid of God. His main work occurred in Germany and Europe. Is it any wonder that the nerve center of Vatican II was located not in Rome, but in Belgium, France, Germany and neighboring Holland and Austria?

Freemasons are allowed to adhere to their personal beliefs, but claim to honor the Grand Architect of the Universe, a concept similar to the Deist, Gnostic and Manichean notion of a god who is a distant observer but who has little impact on one’s life.1 This Grand Architect is not the Blessed Trinity, the Triune God. This ultimately eliminates the need for organized religion.

The liberal concept promoted by Freemasonry called indifferentism claims that one religion is as good as another. Indifferentism was formally adopted at Vatican II in its Decrees on Ecumenism and Religious Freedom (Liberty). Popes Pius VIII, Gregory XVI, Pius IX, Leo XIII, and Pius XI have condemned these erroneous beliefs.

Surprisingly, many clergy joined Freemasonry, as explained by H. Daniel-Rops in his book, The Church in the Eighteenth Century (p. 63):

“At Caudebec [France] fifteen out of eighty members of the lodge were priests; at Sens [France], twenty out of fifty. Canons and parish priests sat in the Venerable Assembly, while the Cistercians of Clairvaux had a lodge within the very walls of their monastery. Saurine, the future bishop of Strasbourg under Napoleon, was among the governing members of the Grand Orient. We cannot be far from the truth in suggesting that towards the year 1789 a quarter of French Freemasons were churchmen…”

These clergy became willing disciples who disseminated pestilent ideas among the masses and in seminaries, religious houses and universities. Neighboring countries soon became infected with liberalism. This ideology is described by Cardinal Newman as a rejection of first principles and Divine Revelation (Sacred Scripture and Apostolic Tradition) that were replaced by reason.

Pope Clement XII condemned Freemasonry and secret societies in 1738, as have ten subsequent popes. Since few have been able to lift its clandestine veil, nearly 300 years of covert activity has remained almost undetected, except for its devastating results: wide-scale doubt and disbelief, rebellion against authority, disregard of the Ten Commandments and often law in general, free thought and action, indifference to God and the supernatural, disregard of past Church teachings including Sacred Scripture and Apostolic Tradition, and focus on the here and now, with nearly total apathy toward a future life.

Since persecution often only brought more converts to the Catholic Church, Freemasons chose to infiltrate it as described by a letter of Piccolo Tigre of 1822:

“…You will bring yourselves as friends around the Apostolic Chair [the pope]. You will have fished up a Revolution in Tiara and Cope, marching with the Cross and banner — a Revolution which will need but to be spurred on a little to put the four corners of the world on fire.

“.. .In the present circumstances never lift the mask. Content yourself to prowl about the Catholic sheepfold, but as good wolves seize in the passage the first lamb who offers himself in the desired conditions. …The conspiracy against the Holy See should not confound itself with other projects.

“…It is of absolute necessity to de-Catholicize the world….The Revolution in the Church is the Revolution en permanence….Let us not conspire except against Rome.”2

Pestilent Ideas

The devil has found that the easiest way to lead souls astray is to offer erroneous teachings. These false beliefs, called heresies, willfully turn one away from God and His laws thereby affecting a person’s determination between right and wrong and truth and error. Venerable Bede says that the devil always mixes a little truth with error to make it more attractive and palatable. Pope St. Pius X compared this to a drop of poison.

Since a compass shows magnetic north, not true north, pilots must compensate; otherwise, they will be led off course. If an individual or society follows false standards and erroneous beliefs, its actions will be morally reprehensible. Sin will be looked upon as good and normal and virtue will be considered extreme and despicable. Vatican II achieved this end.

It only takes a few individuals to influence the masses. University professors, mass media and other experts daily influence the lives of millions. The devil found that one of the easiest ways to mislead Catholics was to utilize wolves dressed like sheep: cardinals, bishops and priests promoting error. When the masterminds of Vatican II taught new beliefs, millions obediently followed since they trusted those who conveyed the message. These evil religious leaders were a conduit used by the forces of Hell to pervert belief and lead the flock astray.

It took years to alter belief, but by gradual laxity, indifference to religion and lack of a prayer life many easily fell into the trap. The spread of erroneous beliefs is like the work of a careful arsonist. Small fires soon engulf the entire forest.

The 1700s

Vatican II embodies many of the ecumenical and Freemasonic concepts of Locke, Hume, Rousseau, Diderot,3 and Voltaire4 that permeated society in the 1700s. This period in Europe, known as the Age of Reason or Age of Enlightenment, attempted to replace religion with philosophy and deify man, causing religious upheaval. It ultimately leads to atheism.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s lack of love for the five children that his mistress and later wife Therese Levasseur bore him was manifested by him sending them, after birth, to a local orphanage. Voltaire (1694-1778) and Diderot (1713-1784) viciously attacked the Catholic Faith and not only the need for, but the very existence of God. Hume (1711-1776) favored sentiment over reason and being an atheist, claimed life should be based on self-gratification, a theory that is practiced by millions today. The work of these men cannot be underestimated.

The Jansenist heresy viewed God as a heartless tyrant and attacked many aspects of the Catholic Faith. Jansenist Abbé Jacques Jubé d’Asnières of France, who died in the Netherlands in 1720, was among several who devised vernacular liturgies that closely resembled the New Mass. This experimentation paved the way for the liturgical changes of Vatican II. The schismatic Council of Pistoia in 1789 attacked the authority of the pope and was condemned by Pope Pius VI in his papal bull, Auctorem Fidei, in 1794.

France was being slowly transformed from a Catholic country into the international center for Freemasonry. The Civil Constitution of the Clergy assured that priests were mere employees of the state who were quickly promoted and easily gained positions of prominence.

During the French Revolution and its aftermath, Church property was confiscated, a schismatic church was created, clergy were encouraged to marry and the celebration of Mass and the confection of the sacraments by clergy loyal to the Catholic Faith was prohibited. The conformist hierarchy and clergy soon became preoccupied with secular interests and neglected the work of souls. Clergy who opposed married clergy and the newly formed schismatic church were exiled or drowned. The French Church that once seemed impregnable soon began to crumble.

The 1800s

Things looked so bleak that some predicted the destruction of the Catholic Church in 1799 when Pope Pius VI died in exile in France. Some French politicians and German freethinkers bragged that this would be the end of the papacy.

The French Concordat of 1801 allowed Catholicism to return to France with certain stipulations. French bishops, henceforth, would be chosen by the state, not nominated by the pope. This greatly helped the Modernists over 150 years later, shortly before Vatican II, since their men were already well-entrenched in positions of power. A number of French prelates, including Daniélou, Elchinger, Etchegaray, Liénart, Lustiger, Marty, Suhard and Weber played major roles before, during and after Vatican II. Four of these Modernists served as Presidents of the Bishops Conference of France.

The Prussian Kulturkampf (cultural struggle) was Otto von Bismarck’s attempt from 1871-1878 to weaken the influence of the Church. Although Catholics comprised nearly 40% of the population, half of the bishops and nearly 2,000 priests were imprisoned or exiled. Laity who assisted them were thrown in jail. During this time, over a million Catholics were deprived of the Mass and sacraments and 25% of parishes were abandoned.

Few ordinations occurred since schools and seminaries were controlled by the government and candidates had to follow state guidelines and attend secular universities. Although the measures were eventually mitigated, as they had been decades earlier in France, the persecution allowed priests and bishops who were sympathetic with the goals of Bismarck to occupy key positions in the hierarchy and train others who became their successors, without suspicion. Remember, this occurred only 90 years before the start of Vatican II.

The University of Tübingen had long been a haven for modern, liberal thought. Johann Möhler (1796-1838), who inspired many future Modernists, was a Tübingen theologian. Liberal Protestant theologian Adolf von Harnack (1851-1930), who is often considered the founder of Modernism, was a Tübingen scholar. Modernist Karl Adam (1876-1966) spent his entire career teaching at Tübingen. Modernist Romani Guardini (1885-1968) was likewise a Tübingen scholar.

The theological schools of Freiburg, Munich, Tübingen, and Würzburg taught Modernism and other erroneous beliefs for decades, but carefully remained under the Vatican radar. They became a nursery of Modernism and prepared the way for Vatican II by training many of its future leaders. Modernism was disseminated throughout Europe by influential leaders who paved the way for Vatican II. Some were condemned as heretics, while a few returned to the Church before death. Some of the most prominent, listed by country, are as follows:

Belgium — Albin Van Hoonacker and Paulin Ladeuze (protected from the Vatican by Cardinal Mercier);

England and Ireland — Friedrich von Hügel, Maude Petre and George Tyrrell;

France — Maurice Blondel, Félicité de Lamennais and Alfred Loisy. Protestant ministers Auguste and Paul Sabatier (another Tübiginen student) suggested that Catholics rebuild the Church from within.

Germany — Herman Schell and Adolf von Harnack;

Italy — Ernesto Buonaiuti, Antonio Fogazzaro, Salvatore Minocchi, Romolo Murri and Giovanni Semeria;

Many early Modernist “theologians” were prolific writers who were highly esteemed in intellectual circles, while priests spread their errors among their peers.

The Architects of Modernism

Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) adopted the hypothesis of David Hume (1711 -1776) that human nature is defective and incapable of grasping the concept of God. This agnostic belief states that God cannot be known from the world He created.

The Lutheran Kant believed that cause and effect, a basic premise of natural theology, is untenable. Divine revelation is also deemed impossible.

Kant imbibed the errors of René Descartes and John Locke that led to the belief that a person cannot know things as they actually are, but only as they appear.

Therefore, if a person could never have formal certitude about anything, even religion, life would become a do-it-yourself project with no manual and no rules. Is it any wonder that the fruits of Vatican II are anarchy, division and constant change?

Felicité de Lamennais (1782-1854) advocated liberation theology and was excommunicated in 1834.

Herman Schell (1848-1906) was professor of apologetics at Würzburg where he gave lectures on Eastern religions, Kant and Nietzsche. The ardent ecumenist called his followers “Progressive Catholics.” Schell advocated the universal priesthood of all baptized believers, opposed scholastic philosophy and despised the Vatican and ecclesiastical authority.

His first book received no imprimatur (approval from Church authority to publish his works) from the Vatican, while three subsequent books were placed on the Index of Forbidden Books.

Pope Leo XIII condemned many of Schell’s heretical beliefs including his denial of the Fall, the eternity of Hell, and both original and mortal sin, his warped concept of the Blessed Trinity, his belief that death was a quasi-sacrament whereby the non-baptized could be saved, and his minimization of the efficacy of both Baptism and Extreme Unction. Pope St. Pius X called his beliefs a new poison.

Contemporary scholar Ernst Commer claimed “there were errors in every area of his theology.”5

Historian Thomas O’Meara, OP, in his work, Church in Culture: German Catholic Thought, 1860-1914, commented that Teilhard de Chardin, Henri de Lubac, Karl Rahner, and Hans Küng merely repackaged Schell’s teachings.

Modernists laud Schell’s erroneous beliefs, many of which are contained in the documents of Vatican II. There was a revival of his works after the Council.

Maurice Blondel (1861-1949), a French lay philosopher, believed in an inner force called vital immanence that opened one to the divine. To him there was little distinction between the natural and supernatural, which he often blended together.

Blondel, like the heretic Pelagius (354- 418), believed that natural actions can merit a supernatural reward. He held that natural goodness was the only quality necessary for a human person. Faith, he believed, was merely an expression of human aspirations.

Chenu, Congar and de Lubac later imbibed and expanded many of Blondel’s heretical beliefs.

Adolf von Harnack (1851-1930) was a liberal Protestant who acted as court theologian in Berlin and claimed the Catholic Church distorted Gospel teachings. He denied the divinity of Christ, whom he believed merely revealed the Father to humanity, and the need for a visible church. His pupil, Karl Barth (1886-1965), who influenced Protestant and Modernist thought throughout the twentieth century, was one of the founders of the World Council of Churches.

Alfred Loisy (1857-1940) was a French apostate priest and biblical scholar who believed in a constantly changing church that developed historically. Loisy taught at the Institut Catholique of Paris from 1890-1893 and denied the authenticity of St. John’s Gospel.

Chenu and Rahner adopted Loisy’s erroneous beliefs that a church gradually developed around the man Jesus. Five of his books were placed on the Index of Forbidden Books by the Holy Office on December 16, 1902. After being excommunicated in March 1908, he began promoting a humanist religion.

Loisy placed “theologians” above God. Interestingly, “theologians” of Vatican II enjoyed celebrity status and were revered above both Scripture and Tradition.

In 1907, Albert Houtin wrote in his Vie de Loisy (p. 138): “I knew that he was no longer a Christian, though he always claimed to be something of a Catholic, but I believed that he was like me a spiritualist and a deist. He told me that twenty years ago he ceased to believe in the soul, in free will, in the future life, in the existence of a personal God.”

George Tyrrell (1861-1909) was an Irish convert who later became a Jesuit priest. He began to read the works of Blondel after befriending Baron Friedrich von Hügel, (1852-1925), a zealous advocate of the Modernist movement. He denied an infallible Deposit of Faith and believed in a developing theology based on individual experience.

Tyrell condemned dogma, the papacy and hierarchy as human institutions and believed in the indwelling of the Holy Spirit among the laity where God resided within the community.

He believed that every baptized person was an official missionary. Yves Congar, OP, transformed this idea into the universal priesthood of believers that is found in Vatican II documents. Lay-run parishes, lay councils, lay distribution of communion, readers, and lay deacons are the result.

According to Tyrell, morality should be based upon popular opinion. Moral relativism pervades society today and has resulted in rampant immorality and practical atheism, making a mockery of the Ten Commandments. The Modern Church de-emphasizes the seriousness of sin. It is looked upon as a mistake, not as an offense against God.

A church devoid of hierarchical structure and with beliefs and morals determined by individuals would ultimately evolve into the universal religion Tyrell envisioned in his posthumous book, Christianity at the Cross-Roads. After being expelled from the Jesuits in 1906, Tyrell claimed he was still alive but that his heart was dead. He was excommunicated two years later. Some believed he eventually became an agnostic.

Modernism

These influential men sowed the seeds of doubt, creating a religion which was dependent upon the individual. Modernists attempted to replace Scripture and Catholic dogma with historical analysis and reason. Even though subsequent popes condemned the errors and warned the faithful, Modernists, like termites, found hidden recesses and continued their work in stealth.

Pope St. Pius X openly attacked Modernism by his encyclical Pascendi, by his Oath Against Modernism and by removing seminary professors who were infected. Others lay low until the 1930s. These men became the leaders, the “experts” at Vatican II.

Footnotes

1 Deist and Gnostic beliefs were condemned during the early ages of the Church and the Albigensian (Manichean) heresy was denounced at the Third Lateran Council in 1179.

2 Alta Vendita (letter by Piccolo Tigre—Little Tiger) written to the Piedmontese lodges of the Carbonari. From Msgr. George Dillon, DD, The War of Antichrist with the Church and Christian Civilization, pp. 65-72, 77, London: Burns & Oates, 1885.

3 His revolutionary and naturalist ideas were even promoted by priests who joined his cause. Diderot’s attacks against God included theories similar to those of Charles Darwin. The Encyclopédie that he edited comprised 17 volumes and was printed between 1751 and 1772.

4 This prolific writer authored 2,000 books and periodicals and 20,000 letters. His death is claimed to have been one of horrible despair. A story has circulated that when a priest asked him to renounce the devil before death, Voltaire is claimed to have said that it was not a good time to make new enemies. Voltaire’s promotion of immorality in the form of sexual license and lack of moral restraint pervade society today.

5 Thomas O’Meary, OP, Church and Culture: German Catholic Theology 1860-1914, p. 115.