An Open Letter to Confused Catholics

Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre

“Vatican II is the French Revolution in the Church.”

The parallel I have drawn between the crisis in the Church and the French Revolution is not simply a metaphorical one. The influence of the philosophes of the eighteenth century, and of the upheaval that they produced in the world, has continued down to our times. Those who have injected that poison into the Church admit it to themselves. It was Cardinal Suenens who exclaimed, “Vatican II is the French Revolution in the Church” and among other unguarded declarations he added “One cannot understand the French or the Russian revolutions unless one knows something of the old regimes which they brought to an end… It is the same in church affairs: a reaction can only be judged in relation to the state f things that preceded it”. What preceded, and what he considered due for abolition, was that wonderful hierarchical construction culminating in the Pope, the Vicar of Christ on earth. He continued: “The Second Vatican Council marked the end of an epoch; and if we stand back from it a little more we see it marked the end of a series of epochs, the end of an age”.

Père Congar, one of the artisans of the reforms, spoke likewise: “The Church has had, peacefully, its October Revolution.” Fully aware of what he was saying, he remarked “The Declaration on Religious Liberty states the opposite of the Syllabus.” I could quote numbers of admissions of this sort. In 1976 Fr. Gelineau, one of the party-leaders at the National Pastoral and Liturgical Centre removed all illusions from those who would like to see in the Novus Ordo something merely a little different from the rite which hitherto had been universally celebrated, but in no way fundamentally different: “The reform decided on by the Second Vatican Council was the signal for the thaw… Entire structures have come crashing down… Make no mistake about it. To translate is not to say the same thing with other words. It is to change the form. If the form changes, the rite changes. If one element is changed, the totality is altered.., of must be said, without mincing words, the Roman rite we used to know exists no more. It has been destroyed.”8

The Catholic liberals have undoubtedly established a revolutionary situation. Here is what we read in the book written by one of them, Monsignor Prelot,9 a senator for the Doubs region of France. “We had struggled for a century and a half to bring our opinions to prevail within the Church and had not succeeded. Finally, there came Vatican Il and we triumphed. From then on the propositions and principles of liberal Catholicism have been definitively and officially accepted by Holy Church.”

It is through the influence of this liberal Catholicism that the Revolution has been introduced under the guise of pacifism and universal brotherhood. The errors and false principles of modern man have penetrated the Church and contaminated the clergy thanks to liberal popes themselves, and under cover of Vatican II.

It is time to come to the facts. To begin with, I can say that in 1962 I was not opposed to the holding of a General Council. On the contrary, I welcomed it with great hopes. As present proof here is a letter I sent out in 1963 to the Holy Ghost Fathers and which has been published in one of my previous books.10 I wrote: “We may say without hesitation, that certain liturgical reforms have been needed, and it is to be hoped that the Council will continue in this direction.” I recognized that a renewal was indispensable to bring an end to a certain sclerosis due to a gap which had developed between prayer, confined to places of worship, and the world of action-schools, the professions and public life. I was nominated a member of the Central Preparatory Commission by the pope and I took an assiduous and enthusiastic part in its two years of work. The central commission had the responsibility of checking and examining all the preparatory schemas which came from the specialist commissions. I was in a good position therefore to know what had been done, what was to be examined, and what was to be brought before the assembly.

This work was carried out very conscientiously and meticulously. I still possess the seventy-two preparatory schemas; in them the Church’s doctrine is absolutely orthodox. They were adapted in a certain manner to our times, but with great moderation and discretion.

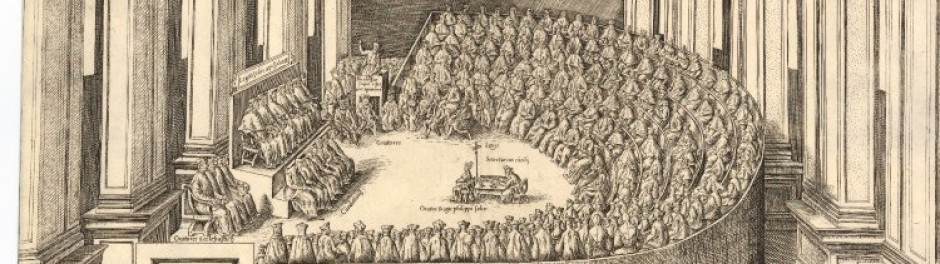

Everything was ready for the date announced and on 11th October, 1962, the Fathers took their places in the nave of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. But then an occurrence took place which had not been foreseen by the Holy See. From the very first days, the Council was besieged by the progressive forces. We experienced it, felt it; and when I say we, I mean the majority of the Council Fathers at that moment.

We had the impression that something abnormal was happening and this impression was rapidly confirmed; fifteen days after the opening session not one of the seventy-two schemas remained. All had been sent back, rejected, thrown into the waste-paper basket. This happened in the following way. It had been laid down in the Council rules that two-thirds of the votes would be needed to reject a preparatory schema. Now when it was put to the vote there were 60% against the schemas and 40% in favor. Consequently the opposition had not obtained the two-thirds, and normally the Council would have proceeded on the basis of the preparations made.

It was then that a powerful, a very powerful organization showed its hand, set up by the Cardinals from those countries bordering the Rhine, complete with a well-organized secretariat. They went to find the Pope, John XXIII, and said to him: “This is inadmissible, Most Holy Father; they want us to consider schemas which do not have the majority,” and their plea was accepted. The immense work that had been found accomplished was scrapped and the assembly found itself empty-handed, with nothing ready. What chairman of a board meeting, however small the company, would agree to carry on without an agenda and without documents? Yet that is how the Council commenced.

Then there was the affair of the Council commissions which had to be appointed. This was a difficult problem; think of the bishops arriving from all countries of the world and suddenly finding themselves together in St. Peter’s. For the most part, they did not know one another; they knew three or four colleagues and a few others by reputation out of the 2400 who were there. How could they know which of the Fathers were the most suitable to be members of the commission for the priesthood, for example, or for the liturgy, or for canon law?

Quite lawfully, Cardinal Ottaviani distributed to each of them the list of the members of the pre-conciliar commissions, people who in consequence had been selected by the Holy See and had already worked on the subjects to be debated. That could help them to choose without there being any obligation and it was certainly to be hoped that some of these experienced men would appear in the commissions.

But then an outcry was raised. I don’t need to give the name of the Prince of the Church who stood up and made the following speech: “Intolerable pressure is being exerted upon the Council by giving names. The Council Fathers must be given their liberty. Once again the Roman Curia is seeking to impose its own members.”

This crude outspokenness was rather a shock, and the session was adjourned. That afternoon the secretary, Mgr. Felici announced, “The Holy Father recognizes that it would perhaps be better for the bishops’ conferences to meet and draw up the lists.”

The bishops’ conferences at that time were still embryonic: they prepared as best they could the lists they had been asked for without, anyway, having been able to meet as they ought, because they had only been given twenty-four hours. But those who have woven this plot had theirs all ready with individuals specially chosen from various countries. They were able to forestall the conferences and in actual fact they obtained a large majority. The result was that the commissions were packed with two-thirds of the members belonging to the progressivist faction and the other third nominated by the Pope.

New schemas were rapidly brought out, of a tendency markedly different from the earlier ones. I should one day like to publish them both so that one can make the comparison and see what was the Church’s doctrine on the eve of the Council.

Anyone who has experience of either civil or clerical meetings will understand the situation in which the Fathers found themselves. In these new schemas, although one could modify a few odd phrases or a few propositions by means of amendments, one could not change their essentials. The consequences would be serious. A text which is biased to begin with can never be entirely corrected. It retains the imprint of whoever drafted it and the thoughts that inspired it. The Council from then on was slanted. A third element contributed to steering it in a liberal direction. In place of the ten presidents of the Council who had been nominated by John XXIII, Pope Paul VI appointed for the last two sessions four moderators, of whom the least one can say is that they were not chosen among the most moderate of the cardinals. Their influence was decisive for the majority of the Council Fathers.

The liberals constituted a minority, but an active and organized minority, supported by a galaxy of modemist theologians amongst whom we find all the names who since then have laid down the law, names like Leclerc, Murphy, Congar, Rahner, Küng, Schillebeeckx, Besret, Cardonnel, Chenu, etc. And we must remember the enormous output of printed matter by IDOC, the Dutch Information Center, subsidized by the German and Dutch Bishops’ Conferences which all the time was urging the Fathers to act in the manner expected of them by international opinion. It created a sort of psychosis, a feeling that one must not disappoint the expectations of the world which is hoping to see the Church come round to its views. So the instigators of this movement found it easy to demand the immediate adaptation of the Church to modern man, that is to say, to the man who wants to free himself of all restraint. They made the most of a Church deemed to be sclerotic, out of date, and powerless, beating their breasts for the faults of their predecessors. Catholics were shown to be more guilty than the Protestants and Orthodox for their divisions of times past; they should beg pardon of their “separated brethren” present in Rome, where they had been invited in large numbers to take part in the activities.

The Traditional Church having been culpable in its wealth and in its triumphalism, the Council Fathers felt guilty themselves at not being in the world and at not being of the world; they were already beginning to feel ashamed of their episcopal insignia; soon they would be ashamed to appear wearing the cassock.

This atmosphere of liberation would soon spread to all areas. The spirit of collegiality was to be the mantle of Noah covering up the shame of wielding personal authority, so contrary to the mind of twentieth century man, shall we say, liberated man! Religious freedom, ecumenism, theological research, and the revising of canon law would attenuate the triumphalism of a Church which declared itself to be the sole Ark of Salvation. As one speaks of people being ashamed of their poverty, so now we have ashamed bishops, who could be influenced by giving them a bad conscience. It is a technique that has been employed in all revolutions. The consequences are visible in many places in the annals of the Council. Read again the beginning of the schema, “ The Church in the Modern World,” on the changes in the world today, the accelerated movement of history, the new conditions affecting religious life, and the predominance of science and technology. Who can fail to see in these passages an expression of the purest liberalism?

We would have had a splendid council by taking Pope Pius XII for our master on the subject. I do not think there is any problem of the modern world and of current affairs that he did not resolve, with all his knowledge, his theology and his holiness. He gave almost definitive solutions, having truly seen things in the light of faith.

But things could not be seen so when they refused to make it a dogmatic council. Vatican II was a pastoral Council; John XXIII said so, Paul VI repeated it. During the course of the sittings we several times wanted to define a concept; but we were told: “We are not here to define dogma and philosophy; we are here for pastoral purposes.” What is liberty? What is human dignity? What is collegiality? We are reduced to analyzing the statements indefinitely in order to know what they mean, and we only come up with approximations because the terms are ambiguous. And this was not through negligence or by chance. Fr. Schillebeeckx admitted it: “We have used ambiguous terms during the Council and we know how we shall interpret them afterwards.” Those people knew what they were doing. All the other Councils that have been held during the course of the centuries were dogmatic. All have combatted errors. Now God knows what errors there are to be combatted in our times! A dogmatic council would have filled a great need. I remember Cardinal Wyszinsky telling us: “You must prepare a schema upon Communism; if there is a grave error menacing the world today it is indeed that. If Pius XII believed there was need of an encyclical on communism, it would also be very useful for us, meeting here in plenary assembly, to devote a schema to this question.”

Communism, the most monstrous error ever to emerge from the mind of Satan, has official access to the Vatican. Its world-wide revolution is particularly helped by the official non-resistance of the Church and also by the frequent support it finds there, in spite of the desperate warnings of those cardinals who have suffered in several of the Eastern countries. The refusal of this pastoral council to condemn it solemnly is enough in itself to cover it with shame before the whole of history, when one thinks of the tens of millions of martyrs, of the Christians and dissidents scientifically de-personalized in psychiatric hospitals and used as human guinea-pigs in experiments. Yet the Council kept quiet. We obtained the signatures of 450 bishops calling for a declaration against Communism. They were left forgotten in a drawer. When the spokesman for Gaudium et Spes replied to our questioning, he told us, “There have been two petitions calling for a condemnation of Communism.” “Two!” we cried, “there are more than 400 of them!” “Really, I know nothing about them.” On making inquiries, they were found, but it was too late.

These events I was involved in. It is I who carried the signatures to Mgr. Felici, the Council Secretary, accompanied by Mgr. de Proenca Sigaud, Archbishop of Diamantina: and I am obliged to say there occurred things that are truly inadmissible. I do not say this in order to condemn the Council; and I am not unaware that there is here a cause of confusion for a great many Catholics. After all, they think the Council was inspired by the Holy Ghost.

Not necessarily. A non-dogmatic, pastoral council is not a recipe for infallibility. When, at the end of the sessions, we asked Cardinal Felici, “Can you not give us what the theologians call the ‘theological note of the Council?’” He replied, “We have to distinguish according to the schemas and the chapters those which have already been the subject of dogmatic definitions in the past; as for the declarations which have a novel character, we have to make reservations.”

Vatican II therefore is not a Council like others and that is why we have the right to judge it, with prudence and reserve. I accept in this Council and in the reforms all that is in full concordance with Tradition. The Society I have founded is ample proof. Our seminaries in particular comply with the wishes expressed by the Council and with the ratio fundamentalis of the Sacred Congregation for Catholic Education.

But it is impossible to maintain it is only the later applications of the Council that are at fault. The rebellion of the clergy, the defiance of pontifical authority, all the excesses in the liturgy and the new theology, and the desertion of the churches, have they nothing to do with the Council, as some have recently asserted? Let us be honest: they are its fruits!

In saying this I realize that I merely increase the worry and perplexity of my readers. But, however, among all this tumult a light has shone forth capable of reducing to nought the attempts of the world to bring Christ’s Church to an end. On June 30, 1968 the Holy Father published his Profession of Faith. It is an act which from the dogmatic point of view is more important than all the Council.

This Credo, drawn up by the successor of Peter to affirm the faith of Peter, was an event of quite exceptional solemnity. When the Pope rose to pronounce it the Cardinals rose also and all the crowd wished to do likewise, but he made them sit down again. He wanted to be alone, as Vicar of Christ, to proclaim his Credo and he did it with the most solemn of words, in the name of the Blessed Trinity, before the holy angels and before all the Church. In consequence, he has made an act which pledges the faith of the Church.

We have thereby the consolation and the confidence of feeling that the Holy Ghost has not abandoned us. We can say that the Act of Faith that sprang from the First Vatican Council has found its other resting point in the profession of faith of Paul VI.

8. Demain la liturgie, ed. du Cerf.

9. Le Catholicisme Libéral, 1969

10. A Bishop Speaks, The Angelus Press