Christendom and Revolution

Fr. Juan Carlos Iscara

Preface for a Catholic Understanding of History

Two cities have been formed by two loves: the earthly by the love of self, even to the contempt of God; the heavenly by the love of God, even to the contempt of self….St. Augustine, The City of God, XIV, 28

This is the history…that Christ calls and wants all beneath His standard, and Lucifer, on the other hand, wants all under his….St. Ignatius of Loyola, Spiritual Exercises, n.136

The Church is Tradition. Essential for her mission of sanctifying, ruling and teaching is the transmission of what she herself has received from her divine Founder, from generation to generation, until the end of time, without change in its essentials. That is what Archbishop. Lefebvre acknowledged to have been his life’s mission: Tradidi quod et accepi I have transmitted what I have received, and the mission he entrusted to the Society of St. Pius X.

Thus, in this sense, this article is to be “traditional,” not original. It does not intend to communicate the more or less sensible reflections of its author about History, but to transmit the concept that the Church has of her life in the world and of the life of the world around her in the light of the immutable revealed principles of which she is the custodian. There is a Christian view of History that has nothing to do with the historical rot we are routinely taught. It is a “theology of history,” a vision sub specie æternitatis, an interpretation of time in terms of eternity, and of human events in the light of divine Revelation. The Church “reads” the succession of events in the light of Faith, and discerns in that bewildering multiplicity the pattern of the providential design of God, ineluctably moving towards the end intended by the Creator from all eternity: our beatitude.

Unfortunately, as individuals, many Catholics ignore or simply reject such a vision. Life in a world molded by Protestantism has allowed some of its tenets to permeate even into our Catholic minds and hearts, particularly the assertions that God’s reality must be theologically distinguished from empirical reality, to preserve the transcendent sacredness of Christian truth, that religious reality is an internal phenomenon, and that the Church is essentially an invisible society of “true believers,” a spiritual thing, which must be separated from the secular world for the integrity and freedom of both. Some Catholics have thus become used to thinking of their Faith as an exclusively private affair of the soul with God, somehow alien to their personal daily activity in the world, and in practice totally independent of the political, economic or cultural life of the world around them. They may still acknowledge the “Social Kingship of Christ” and even pray for its coming, but for them it has become an abstract notion, or a term without content, or an object of “devotion,” or whatever you please, but not a feasible reality.

Moreover, starting from the French revolution, the world we live in has been overwhelmed by Liberalism, the doctrine for which freedom is the fundamental principle by which all things are to be judged and organized. In philosophy and religion, Liberalism is a naturalistic system of thought that, by exalting human dignity beyond its limits, declares that every man has the freedom and the right to choose for himself what he feels is true and good.

Liberalism in religion is the doctrine that there is no positive truth in religion, but that one creed is as good as another…revealed religion is not a truth, but a sentiment and a taste; not an objective fact, not miraculous; and it is the right of each individual to make it say just what strikes his fancy.1

These anti-Christian notions, which as such were long ago condemned by the Church, are now taken for granted as prime principles of thought and action. This widespread acceptance has led the contemporary mind, and many of our fellow Catholics, as Dr. John Rao writes,2 to the conclusion that the Church’s refusal to adapt to and compromise with the modern world is absurd or pointless, and that the Catholic positions on this matter should be either automatically dismissed as irrational or thoroughly revised to force the Church to transcend, at long last, her obsolete “defensive modes,” the Counter-Reformation and the Counter-Revolution.

In fact and in spite of many optimistic assessments and expectations, there is a crisis in the Church and in the world and this crisis is simply the continuation of a perpetual battle. There are new skirmishes, new weapons and ever-renewed armies, but it is the same war. In centuries past, anti-Catholic adversaries opposed the application of Catholic principles to society and politics, while today it is Catholicism itself that is under attack, its substance, its reason for existing. The triumphant revolutionary Liberalism has assured us that there is no returning to those questions which, in its mind, have been settled once and for all. Traditional Catholicism is denounced as hopelessly backward, as a “fundamentalism” almost on a par with Islamic terrorism. In the past, the attacks came from without, with the avowed goal of destroying the Church and the Catholic Faith, while today the attacks come from within, from men of the Church, men who “went out from us but they were not of us,” 3 using more devious and efficacious weapons, under the appearance of good.

Perhaps unknowingly and unwillingly, we have long cooperated with the visible and invisible forces that battle against Christ and His one true Church. The battle still goes on. As long as her enemies subsist and scheme, the Church must fight with the weapons God has given her, Truth and Grace, doctrine and virtue.

The Church will preserve the Spirit of God only on condition of being at war against the contrary spirit, the Spirit of Man. Attacked, she must defend herself: it is her right and her duty. What was said to her Divine Spouse is also her history: Dominare in medio inimicorum. Always Queen, always threatened, on earth she has to be militant.4

It is time to open our eyes, and see reality. The first step is to learn and reflect upon the Catholic view of History, upon how human events must be seen in the light of Faith. Without this light, the succession of events is incoherent and useless the study of History. And once we have seen, then we will have to choose.

Christendom

A Mystery of Faith

God is far above us. He is the infinitely Holy, to Whom no man may draw near and live. He has, nevertheless, revealed to us the highest of secrets, the mystery of the Trinity. We would have known nothing of this if God Himself had not revealed it to us. There is in that sense a coming down of God to us, of Him “who …inhabiteth light inaccessible: whom no man has seen, nor can see.” 5 Yet, this revelation takes place under the veil of Faith, and as such, it is open only to the humble and the pure of heart that He has chosen. The proud and profane world, to a great extent, will not accept His revelation.6

Throughout the history of His chosen people, the revelation of God’s mysteries has been gradual, reaching its climax with the coming of God Himself in the flesh, “the mystery which hath been hidden from ages and generations, but now is manifested to his saints.” 7 The Son has become man, and, in a way which escapes our full understanding, has shown the wholeness of His Father: “he that seeth me, seeth the Father also.” 8

It is this mystery of Christ that the Church transmits to all generations. She herself is the “Mystical Body of Christ,” “and He is the head of the body, the Church.” 9 Indeed, the mission of the Son into the world is continued by the mission of the Apostles (and, therefore, of the Church) into the world: “as the Father hath sent me, I also send you.” 10 As Christ discloses to us His divinity, and as the Church, the Mystical Body of Christ, makes Christ’s mystery known to us, likewise Christendom is, in an analogical manner, a manifestation or revelation of Christ’s mystery. This is what Christendom properly is: the manifestation of Christ’s mystery through the social body of the nations. Christendom is, in an analogical manner, Christ’s incarnation in the socio-political order.

Christendom in Concrete

Christendom is “a social fabric in which religion penetrates down to the last corners of temporal life (customs, uses, games and work…), a civilization in which the temporal is unceasingly infused by the eternal.” 11 Concretely, it is the ensemble of peoples who want to live publicly according to the laws of the Holy Gospel, which is deposited with Mother Church for her to guard it.

In Christendom, there is the certainty that religion and life, united, form an indissoluble whole. Without deserting the world, but without losing sight of the true sense of life, it ordains the whole of human existence towards a unique goal, “adhaerere Deo,” “prope Deum esse,” towards the contact with God, the friendship of God, being convinced that outside Him there is no lasting peace, either for the heart of man or for society or for the community of nations.12

Christendom sees life on earth as a journey towards life everlasting. The teachings of the Faith are the directing principle of civilization —directive of minds, morals, institutions, all activities of men. The supreme science is Theology, which reasons from the teachings of Faith, draws out their consequences and judges of everything in the light of that same Faith. Philosophy remains as such, proceeding from natural reason, but the philosopher, in the same light of Faith, is able to avoid the errors towards which he is inclined because of the wounds of Original Sin. Sciences are the work of human reason, but they are useful to admire the workings of God in His Creation. Literature and the Arts arise from natural talents, but their inspiration is rooted in intelligence and sensibility penetrated by Faith and animated by the love of God and neighbor. Technology and crafts are at the service of a life made for eternity. Political life retains its proper object and finality, the temporal good, and is ruled by temporal powers distinct from the Church. The State is a sovereign power, not directly subordinated to the Church, but the exercise of its temporal tasks is illuminated by the teachings of the Church, promoting and facilitating her apostolate, never forgetting that the earthly life of men is for eternal life.13

Christendom existed from the conversion of Constantine to the French revolution, when the spiritual sovereignty of the Church was completely and formally rejected. Since then, Christendom has progressively disappeared. Only has remained the Church with its external organization, and even that has been now seriously shaken by the present crisis. Many peoples remained Catholic after the revolution, and the residual habits of a Christian order, although weakened and weakening further, survived still. But Christendom is not simply an ensemble of peoples in which Christianity predominates. Christianity may exist without Christendom. Christendom exists only when the individual and social action of Catholics reaches and shapes the political order as such, the very life of a nation. Socially speaking, then, to convert the world means to turn it back into Christendom.

Christendom and Church

Christendom is not the Church. In consequence, although there is only one Church, there may be multiple “Christendoms,” by reason of the diversity inherent in the earthly life of men, according to different times and places. The Church is not tied exclusively to one concrete realization of Christendom. The Church exists even if there is no Christendom (as in the first three centuries of the Christian era), and she continues to save and sanctify men amidst utterly foreign cultures, mentalities, customs and institutions.

History proves to what extent the Church has always respected the distinctive characteristics, the particular and legitimate contributions of different peoples. Faithful to her divine mandate of procuring the salvation of souls, she has always opposed that religious particularism which pretends that revelation and salvation are the prerogative of one civilization rather than of another.14

There is no sin in the Church; whatever is sinful in her members does not belong to her. But Christendom is affected by the sins of its members, who can impose on it grave defects and deviations. All “Christendoms” are imperfect, because men are imperfect. The Church will continue forever with her work of salvation and sanctification, but Christendom, like all things of this world, is perishable. Only the Church will survive all the vicissitudes of History until the end of time.

Revolution

In common use, the term “revolution” is an emphatic synonym for “fundamental change,” a major, sudden, and hence typically violent alteration in government and in related associations and structures. A revolution constitutes a challenge to the established order and the eventual establishment of a new order radically different from the preceding one. In this sense, it is the triumph of a principle subversive of the existing order.

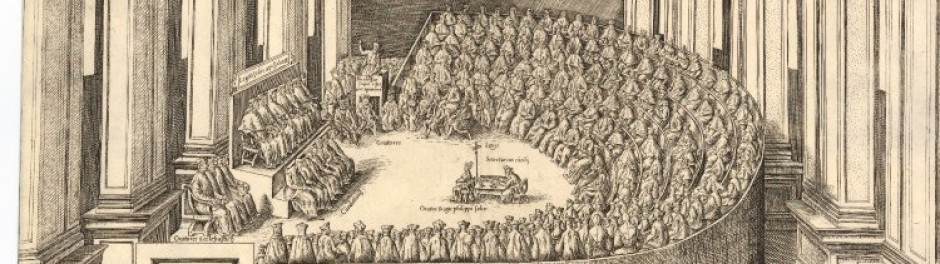

There have always been revolutions in human societies, but Revolution with a capital “R” is (paradoxically) a modern phenomenon. The French revolution in all its stages, from the most moderate to the most cruel, is only a manifestation of Revolution, which is a principle, rather than an event. Revolution is the systematic denial of legitimate authority, it is rebellion raised into a principle and right and law.

I am not what men believe. Many talk about me, but they know me little. I am not Carbonarism… I am not the street riots…or the change of the monarchy for a republic, or the substitution of one dynasty for another, or the temporary perturbation of the public order. I am not the howls of the Jacobins, or the fury of the “Mountain,” or the fight in the barricades, or pillage and arson, or the agrarian laws, or the guillotine and the massacres. I am not Marat, or Robespierre, or Babeuf, Mazzini or Kossuth [or Hitler or Stalin…]. These men are my children, but they are not me. Those actions are my works, but they are not me. These men and those actions are passing events, while I am a permanent state….I am the hatred of any order that has not been established by Man himself, and in which he is not king and god at the same time. I am the proclamation of the rights of Man without any regard for the rights of God. I am God dethroned and Man put in his place. For that reason my name is Revolution, that is, reversal.15

A “Mystery of Iniquity”

From a religious point of view, Revolution can be defined as the legal denial of the reign of Christ on earth, the social destruction of the Church. Revolution necessarily involves the Faith. Our contemporaries have lost a religious sense of the world and of events. Revolution appears therefore essentially as political, and only accidentally as religious. Such a view is erroneous because while Revolution could accommodate any political regime, it is always hostile to Catholicism. He who believes in the divinity of Christ and in the divine mission of the Church (if he is logical) cannot be a revolutionary. All power has been given to Christ, in heaven and on earth, and He has entrusted to the ecclesiastical hierarchy the mission of teaching what is necessary to do the will of God. Therefore, no society can refuse this infallible teaching. The State, as much as the individuals and families, must obey God in its laws and institutions. On the other hand, he who does not believe in the divine mission of the Church usually concludes that she tyrannically encroaches upon the freedom and the rights of man, and, therefore, labors to bring her down to liberate man. The die, then, is cast, and there is no room for neutrality. “He that is not with me is against me; and he that gathereth not with me scattereth.” 16

Revolution itself is a faith. It is faith in the inevitable progress of mankind towards a new order, a better world, to be achieved solely by human effort, without the intervention of God. It is faith in the possibility of realizing here on earth, by natural means, what cannot be realized except in eternity, by supernatural means.17

Revolution is a “mystery of iniquity.” Satan is the father of all rebellions. “Non serviam!” The Revolution begun in Heaven is perpetuated in mankind under the action of Satan. The Fall introduced the spirit of pride and revolt, which is the principle of Revolution. The evil has grown, burrowing deeper in the hearts and minds of men and in the fabric of societies, from ancient heresies and medieval laicism to Humanism and Protestantism, to the Enlightenment and Rousseau, until it took institutional form in the French revolution. From hence, proceeding towards the heart of the Church, the end is in sight:

“The French revolution is the precursor of a greater revolution, more solemn, which will be the last.” 18

The essence of Revolution is satanic; its goal is the destruction of the Kingdom of God on earth. Blessed Pius IX has said it clearly:

“The Revolution is inspired by Satan himself. Its goal is the destruction of the building of Christianity, to reconstruct upon its ruins the social order of paganism.” 19

Revolution is, then, a religious mystery anti-Catholicism. The children of the Revolution have made this equally clear:

“Catholicism must fall! It is not a question of refuting Papism, but of extirpating it not only to extirpate it, but to dishonor it not only to dishonor it, but to smother it in the muck.” 20

The Church, enlightened by Christ and being thus alone in understanding the true character of the Revolution, has since the beginning been its natural enemy.

Perpetual Conflict

The Christian view of History is not merely a belief in the direction of historical events by Divine Providence, but also a belief in the intervention of God in the life of mankind by direct action at certain definite points in time and place. The Incarnation, the central doctrine of the Faith, is also the center of History, giving a spiritual unity to the whole historic process. As St. Irenaeus pointed out, there is a necessary relation between the divine Unity and the unity of History: “…there is one Father the Creator of man, and one Son who fulfills the Father’s will, and one human race in which the mysteries of God are worked out so that the creature conformed and incorporated with His Son is brought to perfection.”

After a providential preparation in the old Dispensation, Christ came in the “fullness of time.” 21 From the moment of the Annunciation, Calvary, Easter and Pentecost, we live in this absolute fulfillment. Christ is the pivot of History, revealing that the succession of events is not a fatalistic chain of causes and effects, but has been ordained by God from all eternity. Theologically speaking, then, the history of the world is no more than the realization of the divine purpose for and in mankind, and, concomitantly, the history of the war between Christ and Satan, between His Church and the Revolution.

Realities

There are three realities confronted in History.22 On one side, the City of God, as Christ has made it forever: holy, immaculate, invincible, destined to be configured to Him by the Cross and charity, destined to carry her cross all the time of her earthly pilgrimage, but assured of her infallible victory through the Cross. On the other side, the City of Satan, her enemy, with its false doctrines and its seductions, a divided City of conflict and hatred, united only in its opposition to God, always enraged against the City of God, seemingly victorious at times, but always ending in failure. And in between, the “carnal cities,” our countries and civilizations, which, although having only an earthly finality, are never neutral: knowingly or not, they are under the dependence of either the City of God or the City of Satan.

As we are living in this “fullness of time,” there is no question of expecting something beyond the redeeming Incarnation of the Son of God, or of altering the immutable constitution of the Church, given by God Himself. The Church will always have sinners and traitors; she will always have to carry the Cross with her Spouse. The earthly cities will never become an earthly paradise; the diabolic poisons will always infect them, and the Church will unceasingly try to heal them, inspiring their restoration in conformity to the law of Christ. The continuation of History, the trials and victories of the Church, the efforts of Christendom, all these exist in view of the perfection of the Mystical Body.

Even the wars, persecutions and all the other evils which have made the history of empires terrible to read and more terrible to live through, have had only one purpose: they have been the flails with which God has separated the wheat from the chaff, the elect from the damned. They have been the tools that have fashioned the living stones which God would set in the walls of His City.23

However, the succession of centuries has also an earthly, temporal, secondary finality: to allow human nature to develop all her potentialities in the work of civilization. But the supreme finality of History is eternal: the manifestation, through the Church, of the glory of Christ and of the power of His Cross,24 until the longed-for day when, the fidelity of the Church consummated in the tribulations of the end of Time, the Lord will make History cease, introduce His Bride in the heavenly Jerusalem, and shut up the Devil and his lackeys “in the eternal lake of fire and sulphur, in the place of the second death.” 25

Stages

Certain stages can be discerned in that continual war between Christ and Satan. Already in 1310, Abbot Engelbert of Admont described, according to the thought of St. Paul,26 the principle of secession at work within Christendom in his times: the mind without the Faith, the Christian community severed from the Holy See, the kingdoms rejecting the Christian order to follow each one its way in isolation.27 Since the 14th century, in particular, attack has followed upon attack, alternately aimed at Christendom and at the Church.

First, the minds and hearts of men were detached from the guidance of the Church. Rationalism, since the Middle Ages and through Humanism and the Enlightenment, taught men to trust only in their own reason, and while the Faith was increasingly doubted, the Protestant rebellion contested and rejected the moral authority upon which all depended. Once this was achieved, Rousseau and Romanticism reacted against reason, teaching men to trust only in their feelings, in their passions. At the end of this process, men were left at the whim of the movements of their own fallen nature, acknowledging no authority and no order external to themselves.

Second, the Catholic states were undermined. The corruption took hold first in the individual members of leading classes, seeping down from the aristocracy to the intellectuals and to the bourgeoisie. It only needed a push to bring the rotten tree down, which had been invisibly rotten for a long time: the French Revolution, the Napoleonic invasions, the organization of new kingdoms and the poisoning of new peoples with the principles of the revolution.

Third, the attack against the heart of the Church came when the Catholic kingdoms, ramparts of the Church, had been overwhelmed. First she was attacked externally in her temporal sovereignty to leave her at the whim of the political powers hostile to her. This brought her back to her beginnings, suffering the persecutions and interferences of the civil power. Once the Church was under siege by a hostile world, pressure was brought upon her through her elite, the clergy. Such was (and is) the work of Modernism, the ever-increasing desire for an accommodation with the modern world, which has led to the aggiornamento of Vatican II and the present secularization of the Faith.

Delusion of Compromise

The French revolution consolidated and gave institutional expression to the principle of Revolution, shaping in this manner our modern world. From that moment on, many Catholics have sought in vain to reconcile what is irreconcilable: the principles of Catholicism and of the Revolution. After the Second Vatican Council, this general tendency has become a permanent turn of mind of (easily) most of our Catholic contemporaries (of the clergy even more than of the laity), expressed in multiple formulas, but grounded on the same ideas —the reconciliation of the revolutionary “human rights” with the Law of God, the acceptance of the principles of secularism and tolerance, and the conviction that such a course of action is the only possibility and hope for the Church in our times.

The present crisis is not new, it did not start with Vatican ii, but it is the end result of a long history of plots and blunders, cunning and weaknesses. Consequently, its solution does not consist in turning back the historical clock to the “good old times” on the eve of the Council.

No compromise is possible with the Revolution. Catholic Truth is by nature intolerant. It cannot coexist with its negation. The Revolution is anti-Christian. It has no notion of Truth or of Common Good; therefore, habitually it cannot (does not) procure either truth or good, and anything true or good in it is merely accidental. Many times, Catholics have fallen into the delusion of presuming the good will of the adversary. Objectively, such “good will” does not exist (although the adversary may be subjectively sincere and kind).

The Revolution cannot be fought with its own weapons. There is an organic, indissoluble bond between the tree and its fruits —agere sequitur esse, “the actions of any being spring up from its nature.” Institutions and laws correspond to the principles from which they issue. They cannot be used to bring about results contrary to that for which they have been created. The modern “liberties,” and the “democratic” institutions in which they are enshrined, will not restore a Christian society. It may happen that some good result is obtained through them, but that can only be an accident, not the rule.

On the contrary, their use will taint our principles. The Revolution is more skilled in their use, while for us those weapons are foreign. The road of compromise is a slippery slope. Once we have compromised, we need to keep going until some results have been achieved —if not, the sacrifices made until now will be a pure loss. Such need to obtain results leads, in turn, to greater compromises. Compromise is, moreover, tainted and accompanied by errors of judgment, imprudence, confusion, obstinacy, and blindness. Ultimately, the compromisers will see as the worst enemies of the common good those who still hold to the true principles.

Counter-Revolution

If the world is to be converted, Christendom has to be rebuilt —not a servile copy of the past, but a “creative imitation,” adapted to our times, of the same eternal Model.

The Church has not to sever herself from the past, she has only to take up again the organisms destroyed by the Revolution, and, in the same Christian spirit which inspired them, adapt them to the new situation created by the material development of contemporary society: for the true friends of the people are neither revolutionaries nor innovators, but traditionalists.28

The Task Ahead

The preliminary battle of the present day is, above all, doctrinal —true doctrine has to be opposed to false doctrine, the Christian ideal to the revolutionary ideal, Catholicism to the Revolution.29 Any intellectual disorder has consequences in the moral and even material orders. Evil therefore has to be fought in its source, the ideas. Amidst the widespread confusion, we must be men of doctrine, having —according to our possibilities —a personal and detailed knowledge of doctrine, studied in the Fathers, in Tradition, and in the Magisterium. Doctrine will arm us for the higher battle, for tearing the Revolution out of our hearts and minds, and out of the world that surrounds us.

Our first duty is to tear the Revolution out of our hearts. Today many Catholics do not consider themselves as they really are, as one with Christ, moved by Him as a body for the molding and transformation of society into Christendom, and have submitted to the pervading and false Protestant separation between “spiritual” life and daily life. As a consequence, they have been lulled into indolence by the pleasing easiness of a world organized against the designs of God, while deluding themselves with their purely internal devotion to Our Lord. “We die because of the Revolution, and because each one of us has been willing to keep this poison in our veins.” 30 On this earth, there are two Cities, perpetually at war, and there is no possible neutrality for any individual —acceptance of one necessarily means war against the other. The Revolution is evil, it is the seed of destruction for nations and families, for souls as well as for bodies. As an evil, it has to be hated and fought with and through the principles of the Church.

Our second duty is to tear the Revolution out of our minds. We must restore in our own minds the Catholic notions and principles, in their integrity:

- The notions of Truth and error, of Good and evil, and their adequate distinctions,

- The notion of Law and its necessary agreement, to be just, with Divine Law,

- The notion of Right and its necessary conformity to our Ultimate End,

- The principle of Authority, which is at the foundation of the natural and supernatural orders, and in direct contradiction to the revolutionary notion of freedom,

- The notion of Hierarchy, the hierarchy of rights and of persons, of Church and State, which is in direct contradiction to the revolutionary principle of equality,

- The notion of Tradition, as directly opposed to the revolutionary desire for novelties.

We must assimilate, as far as possible, the whole Catholic Truth. “We must be frankly, wholly Christian, in belief and in practice —we must affirm the whole doctrinal law and the whole moral law.” 31 In practice, as recommended by the Popes, this means to restore the doctrine of St. Thomas Aquinas to its pre-eminent place as the foundation of our intellectual edifice.

Our third duty is to make all possible efforts to tear the Revolution out of the world around us. Once we have completed the restoration in ourselves, we must extend it around us, using all means available to refute and reject the revolutionary errors, to propagate Catholic Truth. In this manner, and in the measure of our forces, we will be doing our part in the restoration of Christendom. “Many desire the recovery of society, but without a social profession of Faith. At this price, Christ, Omnipotent as He is, cannot work our deliverance; Merciful as He is, He cannot exercise His mercy.” 32 We must affirm the Truth unceasingly, with sincerity, with strength and courage, not only with words, but with our own moral life.

It is necessary to attack, to demolish the citadels of the enemy to save our own fortresses. Foreign doctrines must be overthrown to maintain the faith of the people in our Christian doctrine. Destruenda sunt aliena ut nostris credatur.33

Doctrinal Intolerance

The doctrine must be transmitted without diminution or compromise. It is a disastrous condescendence to abandon doctrine for the sake of peace. “We perish perhaps more in reason of the truths that good men do not have the courage to utter, than from the errors multiplied by evil men.” And these words of Louis Veuillot are a sharp rebuke to modern Catholic leaders, enmeshed in a “dialogue” without issue with the adversaries of the Church:

It is not our religion that you make lovable to them, only your persons. And your fear of ceasing to be loved has ended by taking away your courage to tell the truth. They may praise you, but why? Because of your silences and your denials….34

To silence Catholic doctrine out of a misguided “charity” for those who are in error is to debase ourselves with them.

Everybody sees and acknowledges the abasement of all things since we have abandoned the heights on which Christianity had placed us —nobody can deny it, the abasement of the spirit, of the hearts, of the characters, the abasement of the family, of political power, of societies, briefly, the complete abasement of men and institutions.

The ending of so many abasements cannot be in the abasement also of Truth, which is the only principle that can impress on men and institutions the impulse to re-ascend. We have to beg those who are oracles of doctrine never to have the weakness to consent to any complacency, to any compromise. We have to beg them to tell us in the future the whole Truth, the Truth that saves individuals and nations. Their weakness will be the consummation of our ruin. Then, let us not demand of the Church of Jesus Christ to descend with us “ad ima de summis,” but let us require her to remain there where she is and reach out to us her hand, so as that we can ascend with her “ad summa de imis,” from the low and agitated region into which we have fallen and where we risk descending even more, from here to the elevated and serene region where she inhabits with the souls and the nations that are faithful to her.35

It is the essence of Truth not to tolerate its contradiction —the affirmation of a proposition excludes the negation of the same proposition. When Truth is known, it is necessarily intolerant. Tolerance is self-annihilation, because Truth cannot coexist with its negation. Religious truth being the most absolute and important, it is the most intolerant.36

But although the Church invariably teaches truth and virtue, never consenting to error and evil, she takes pains to make her teaching lovable, treating with indulgence the wanderings provoked by weakness. A loving Mother, the Church never confuses error with the man who is in error, nor the sin with the sinner. She condemns the error, but continues to love the erring man. She fights sin, but pursues the sinner with her tenderness; she desires to make him whole, to reconcile him with God, to bring his heart back to peace and virtue. Thus, the Church commands us to be intolerant, exclusive, in matters of doctrine; that is, to profess this doctrinal intolerance and to be proud of it. But, at the same time, she directs us to make ours the prayer of St. Augustine, “O Lord, send into my heart the sweetness, the softening of Thy Spirit, so that while carried away by the love of Truth, I will not come to lose the truth of Love” 37 —for the union of minds in the Faith is indissolubly united to the union of hearts in Charity and Justice.

In the Hands of God

The Revolution, with its naturalism, secularism and liberalism, is always alive, always growing and penetrating more and more deeply. Today, it seems triumphant.

In the last times, [the] external reign [of the Church] would appear to decline. The Prophets had said: “Bellabunt adversus te et non praevalebunt” (Jer. 1:49). “They will wage war against thee, and they will not prevail.” But the Prophet of the last age has other language: “Datum est bestiae bellum facere cum sanctis et vincere eos” (Apoc. 13:7): “It has been given to the Beast the power to wage war against the Saints and to defeat them,” but this last-moment victory will be the prelude of its coming defeat and definitive ruin….38

Thus, comforted with this promise, we must oppose the Revolution with our incessant refutation of its errors. We must reject the temptation of keeping quiet because there is no reason to disturb the peace when there is no human possibility of success.39 Peace is disturbed only by falsehood. When Truth wages war, it is to restore peace.

The apparent impossibility of human success should in no way deter us. It is not our responsibility to achieve the longed-for restoration —the extirpation of the power of the Beast and the restoration of the rights of God —but to open the way for it, making it possible by believing in the power and mercy of God. As Louis Veuillot wrote, in the dark hours of more than a century ago,

Let us imagine the worst; let us grant that the flood of irreligion has all the strength it boasts of, and that this strength can sweep us away. Well, then, it will sweep us away! It is of no importance, provided that it does not sweep away the Truth. We will be swept away, but we will leave the Truth behind us, as those who were swept away before us left it….Either the world still has a future, or it has not. If we are arriving at the end of time, we are building only for our eternity. But if still long centuries must unfold, by building for eternity we are building also for our time. Whether confronted by the sword or by contempt, we must be the strong witnesses of the Truth of God. Our testimony will survive. There are plants that grow invincibly under the hand of the Heavenly Father. There where the seed is planted, a tree takes root. There where the martyr’s bones lie, a church rises. Thus are formed the obstacles that divide and stop the floods.40

Fr. Juan Carlos Iscara, a native of Argentina, was ordained in 1986 by Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre. For the last ten years he has been teaching Moral Theology and Church History at St. Thomas Aquinas Seminary, Winona, MN.

Footnotes

1.Cardinal Newman, quoted in E.E. Reynolds, Three Cardinals (London: Burns & Oates, 1958), p.16, note 1.

2. See his Removing the Blindfold, an excellent work that must be read to understand how we have reached the present crisis.

3. Jn. 2:19

4. Cardinal Pie

5. I Tim. 6:16

6. These paragraphs are based upon original notes given to the author by Fr. Carlos Urrutigoity.

7. Col. 1:26

8. Jn. 14:9

9. Col. 1:18

10. Jn. 20:21

11. Gustave Thibon, in Calvet, 11

12. Pius XII, Address for the Canonization of St. Nicolas de Flüe, 1947, May 16, in Civilisation Chrétienne, 16-17.

13. See Daujat, passim

14. Letter of Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli to the “Semaine Sociale de Versailles,” 1936, July 10, in Civilisation Chrétienne, 10.

15. Gaume, Révolution, vol. I, 18

16. Lk. 11:23

17. Le Caron, 15

18. François-Noël “Gracchus” Babeuf, French journalist and professional revolutionary who advocated radical agrarian reform and absolute egalitarianism; guillotined in 1797. Quoted in Ségur, 18.

19. Alloc. “Nobis et nobiscum,” quoted in Ségur, 19

20. Edgar Quinet (1803-1875), French poet, Liberal historian and political philosopher, for a while professor at the Collège de France, from which he attacked the Church and exalted the Revolution. Quoted in Ségur, 24.

21. Galatians 4:4: “But when the fullness of time was come, God sent His Son, made of a woman, made under the law…” Eph. 1:10. “In the dispensation of the fullness of the times, to re-establish all things in Christ, that are in heaven and on earth, in Him.”

22. These two paragraphs follow closely Calmel, 10-12.

23. Thomas Merton, in Augustine, x

24.Calmel, 12

25. Calmel, 11-12; Apocalypse 21-22

26. II Thess. 2:3

27. Henri, Daniel-Rops, Cathedral and Crusade (London: J.M. Dent & Sons, 1963) [reprint], 566

28. St. Pius X, Notre Charge Apostolique

29. This program for counter-revolutionary action is briefly summarized from Roul, 521-532

30. Louis Veuillot, quoted in Roul, 524

31. Cardinal Pie, Oeuvres pastorales, vol. 9, p. 227

32. Cardinal Pie, quoted in Ousset, 485

33. Cardinal Pie

34. Quoted in Roul, 523

35. Cardinal Pie, quoted in Théotime de St.-Just, 220-221

36. See Cardinal Pie, “On Doctrinal Intolerance.”

37. Quoted in Cardinal Pie, “On Doctrinal Intolerance.”

38. Cardinal Pie

39. Cardinal Pie, “Pastoral Instruction on the Duty to Confess Publicly the Faith.”

40. Veuillot, 66-67