How The Liturgy Fell Apart: The Enigma Of Archbishop Bugnini

Michael Davies

Archbishop Annibale Bugnini, who died in Rome on 3 July 1982, was described in an obituary in The Times as “one of the most unusual figures in the Vatican’s diplomatic service.” It would be more than euphemistic to describe the Archbishop’s career as simply “unusual”. There can be no doubt at all that the entire ethos of Catholicism within the Roman Rite has been changed profoundly by the liturgical revolution which has followed the Second Vatican Council.

As Father Kenneth Baker SJ remarked in his editorial in the February 1979 issue of the Homiletic and Pastoral Review: “We have been overwhelmed with changes in the Church at all levels, but it is the liturgical revolution which touches all of us intimately and immediately.”

Commentators from every shade of theological opinion have argued that we have undergone a revolution rather than a reform since the Council. Professor Peter L. Berger, a Lutheran sociologist, insists that no other term will do, adding: “If a thoroughly malicious sociologist, bent on injuring the Catholic community as much as possible had been an adviser to the Church, he could hardly have done a better job.”

Professor Dietrich von Hildebrand expressed himself in even more forthright terms: “Truly, if one of the devils in C.S. Lewis’ The Screwtape Letters had been entrusted with the ruin of the liturgy he could not have done it better.”

Major Conquest

Archbishop Bugnini was the most influential figure in the implementation of this liturgical revolution, which he described in 1974 as “a major conquest of the Catholic Church.”

The Archbishop was born in Civitella de Lego, Italy, in 1912. He was ordained into the Congregation for the Missions (Vincentians) in 1936, did parish work for ten years, in 1947 he became active in the field of specialized liturgical studies, was appointed Secretary to Pope Pius Xll’s Commission for Liturgical Reform in 1948, a Consultor to the Sacred Congregation of Rites in 1956; and in 1957 he was appointed Professor of Sacred Liturgy in the Lateran University.

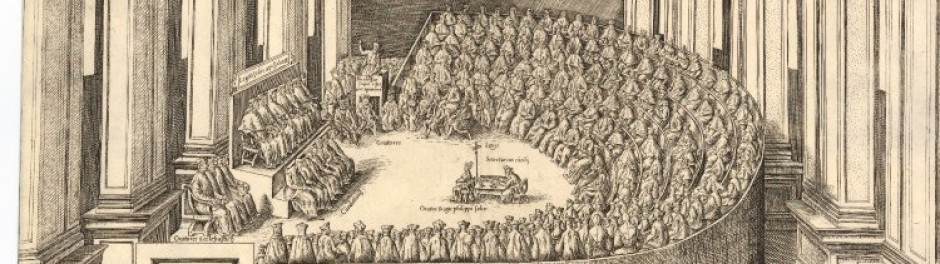

In 1960 Father Bugnini was placed in a position which enabled him to exert a decisive influence on the future of the Catholic Liturgy: he was appointed Secretary to the Preparatory Commission for the Liturgy of the Second Vatican Council. He was the moving spirit behind the drafting of the preparatory schema, the draft document which was to be placed before the Council Fathers for discussion. It was referred to as the “Bugnini schema” by his admirers, and was accepted by a plenary session of the Liturgical Preparatory Commission in a vote taken on 13 January 1962.

The Liturgy Constitution for which the Council Fathers eventually voted was substantially identical to the draft schema which Father Bugnini had steered successfully through the Preparatory Commission in the face of considerable misgivings on the part of Cardinal Gaetano Cicognani, President of the Commission.

The First Exile

Within a few weeks of Father Bugnini’s triumph his supporters were stunned when he was summarily dismissed from his chair at the Lateran University and from the secretaryship of the Liturgical Preparatory Commission. In his posthumous La Riforma Liturgica, Archbishop Bugnini blames Cardinal Arcadio Larraona for this action, which, he claims, was unjust and based on unsubstantiated allegations. “The first exile of P. Bugnini” he commented, (p.41).

The dismissal of a figure as influential as Father Bugnini could not have taken place without the approval of Pope John XXIII, and, although the reasons have never been disclosed, they must have been of a very serious nature. Father Bugnini was the only secretary of a preparatory commission who was not confirmed as secretary of the conciliar commission. Cardinals Lercaro and Bea intervened with the Pope on his behalf, without success.

The Liturgy Constitution, based loosely on the Bugnini schema, contained much generalized and, in places ambiguous terminology. Those who had the power to interpret it were certain to have considerable scope for reading their own ideas into the conciliar text. Cardinal Heenan of Westminster mentioned in his autobiography A Crown of Thorns that the Council Fathers were given the opportunity of discussing only general principles:

“Subsequent changes were more radical than those intended by Pope John and the bishops who passed the decree on the Liturgy. His sermon at the end of the first session shows that Pope John did not suspect what was being planned by the liturgical experts.” The Cardinal could hardly have been more explicit.

The experts (periti) who had drafted the text intended to use the ambiguous terminology they had inserted in a manner that the Pope and the Bishops did not even suspect. The English Cardinal warned the Council Fathers of the manner in which the periti could draft texts capable “of both an orthodox and modernistic interpretation.” He told them that he feared the periti, and dreaded the possibility of their obtaining the power to interpret the Council to the world. “God forbid that this should happen!” he exclaimed, but happen it did.

On 26 June 1966 The Tablet reported the creation of five commissions to interpret and implement the Council’s decrees. The members of these commissions were, the report stated, chosen “for the most part from the ranks the Council periti”.

The Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy was the first document passed by the Council Fathers (4 December 1963), and the commission to implement it (the Consilium) had been established in 1964.

Triumphant Return

In a gesture which it is very hard to understand, Pope Paul Vl appointed to the key post of Secretary the very man his predecessor had dismissed from the same position on the Preparatory Commission, Father Annibale Bugnini. Father Bugnini was now in a unique and powerful position to interpret the Liturgy Constitution in precisely the manner he had intended when he masterminded its drafting.

In theory, the Consilium was no more than an advisory body, and the reforms it devised had to be approved by the appropriate Roman Congregation. In his Apostolic Constitution, Sacrum Rituum Congregatio (8 May 1969), Pope Paul Vl ended the existence of the Consilium as a separate body and incorporated it into the Sacred Congregation for Divine Worship. Father Bugnini was appointed Secretary to the Congregation, and became more powerful than ever. He was now in the most influential position possible to consolidate and extend the revolution behind which he had been the moving spirit and principle of continuity. Nominal heads of the Consilium and congregations came and went, Cardinals Lercaro, Gut, Tabera, Knox, but Father Bugnini always remained. His services were rewarded by his consecration as an Archbishop in 1972.

Second Exile

In 1974 he felt able to make his celebrated boast that the reform of the liturgy had been a “major conquest of the Catholic Church”. He also announced in the same year that his reform was about to enter into its final stage: “The adaptation or ‘incarnation’ of the Roman form of the liturgy into the, usages and mentality of each individual Church.” In India this “incarnation” has reached the extent of making the Mass in some centers appear more reminiscent of Hindu rites than the Christian Sacrifice.

Then, in July 1975, at the very moment when his power had reached its zenith, Archbishop Bugnini was summarily dismissed from his post to the dismay of liberal Catholics throughout the world. Not only was he dismissed but his entire Congregation was dissolved and merged with the Congregation for the Sacraments.

Desmond O’Grady expressed the outrage felt by liberals when he wrote in the 30 August 1972 issue of The Tablet: “Archbishop Annibale Bugnini, who as Secretary of the abolished Congregation for Divine Worship, was the key figure in the Church’s liturgical reform, is not a member of the new congregation. Nor, despite his lengthy experience, was he consulted in the planning of it. He heard of its creation while on holiday in Fiuggi … the abrupt way in which this was done does not augur well for the Bugnini line of encouragement for reform in collaboration with local hierarchies … Mgr Bugnini conceived the next ten years’ work as concerned principally with the incorporation of local usages into the liturgy … He represented the continuity of the post-conciliar liturgical reform.”

The 15 January 1976 issue of L’Osservatore Romano announced that Archbishop Bugnini had been appointed Apostolic Pro Nuncio in Iran. This was his second and final exile.

Conspirator Or Victim?

Rumors soon began to circulate that the Archbishop had been exiled to Iran because the Pope had been given evidence proving him to be a Freemason. This accusation was made public in April 1976 by Tito Casini, one of Italy’s leading Catholic writers. The accusation was repeated in other journals, and gained credence as the months passed and the Vatican did not intervene to deny the allegations. (Of course, whether or not Archbishop Bugnini was a Freemason, in a sense, is a side issue compared with the central issue – the nature and purpose of his liturgical innovations.)

As I wished to comment on the allegation in my book Pope John’s Council, I made a very careful investigation of the facts, and I published them in that book and in far greater detail in Chapter XXIV of its sequel, Pope Paul’s New Mass, where all the necessary documentation to substantiate this article is available. This prompted a somewhat violent attack upon me by the Archbishop in a letter published in the May issue of the Homiletic and Pastoral Review, in which he claimed that I was a calumniator, and that I had colleagues who were “calumniators by profession”.

I found this attack rather surprising as I alleged no more in Pope John’s Council than Archbishop Bugnini subsequently admitted in La Riforma Liturgica. I have never claimed to have proof that Archbishop Bugnini was a Freemason. What I have claimed is that Pope Paul Vl dismissed him because he believed him to be a Freemason – the distinction is an important one. It is possible that the evidence was not genuine and that the Pope was deceived.

Dossier

The sequence of events was as follows. A Roman priest of the very highest reputation came into possession of what he considered to be evidence proving Mgr Bugnini to be a Mason. He had this information placed in the hands of Pope Paul Vl by a cardinal, with a warning that if action were not taken at once he would be bound in conscience to make the matter public. The dismissal and exile of the Archbishop followed.

In La Riforma Liturgica, Mgr Bugnini states that he has never known for certain what induced the Pope to take such a drastic and unexpected decision, even after “having understandably knocked at a good many doors at all levels in the distressing situation that prevailed” (p. 100). He did discover that “a very high-ranking cardinal, who was not at all enthusiastic about the liturgical reform, disclosed the existence of a ‘dossier’, which he himself had seen (or placed) on the Pope’s desk, bringing evidence to support the affiliation of Mgr Bugnini to Freemasonry (p.101). This is precisely what I stated in my book, and I have not gone beyond these facts. I will thus repeat that Pope Paul Vl dismissed Archbishop Bugnini because he believed him to be a Mason.

Rumor

The question which then arises is whether the Archbishop was a conspirator or the victim of a conspiracy. He was adamant that it was the latter: “The disclosure was made in great secrecy, but it was known that the rumor was already circulating in the Curia. It was an absurdity, a pernicious slander. This time, in order to attack the purity of the liturgical reform, they tried morally to tarnish the purity of the secretary of the reform” (p.101-102).

Archbishop Bugnini wrote a letter to the Pope on 22 October 1975 denying any involvement with Freemasonry, or any knowledge of its nature or its aims. The Pope did not reply. This is of some significance in view of their close and frequent collaboration from 1964. The great personal esteem that the Pope had felt for the Archbishop is proved by his decision to appoint him as Secretary to the Consilium, and later to the Sacred Congregation for Divine Worship, despite the action taken against him during the previous pontificate.

Evidence

It is also very significant that the Vatican has never given any reason for the dismissal of Archbishop Bugnini, despite the sensation it caused, and it has never denied the allegations of Masonic affiliation. If no such affiliation had been involved in Mgr Bugnini’s dismissal, it would have been outrageous on the part of the Vatican to allow the charge to be made in public without saying so much as a word to exonerate the Archbishop.

I was able to establish contact with the priest who had arranged for the “Bugnini dossier” to be placed into the hands of Pope Paul Vl, and I urged him to make the evidence public. He replied: “I regret that I am unable to comply with your request. The secret which must surround the denunciation (in consequence of which Mgr Bugnini had to go!) is top secret and such it has to remain. For many reasons. The single fact that the above mentioned Monsignore was immediately dismissed from his post is sufficient. This means that the arguments were more than convincing.”

I very much regret that the question of Mgr Bugnini’s possible Masonic affiliation was ever raised as it tends to distract attention from the liturgical revolution which he masterminded. The important question is not whether Mgr Bugnini was a Mason but whether the manner in which Mass is celebrated in most parishes today truly raises the minds and hearts of the faithful up to almighty God more effectively than did the pre-conciliar celebrations. The traditional Mass of the Roman Rite is, as Father Faber expressed it, “the most beautiful thing this side of heaven.” The very idea that men of the second half of the twentieth century could replace it with something better, is, as Dietrich von Hildebrand has remarked, ludicrous.

Liturgy Destroyed

The liturgical heritage of the Roman Rite may well be the most precious treasure of our entire Western civilization, something to be cherished and preserved for future generations. The Liturgy Constitution of the Second Vatican Council stated that: “In faithful obedience to tradition, the sacred Council declares that Holy Mother Church holds all lawfully recognized rites to be of equal right and dignity, that she wishes to preserve them in future and foster them in every way.”

How has this command of the Council been obeyed? The answer can be obtained from Father Joseph Gelineau SJ, a Council peritus, and an enthusiastic proponent of the postconciliar revolution. In his book Demain la liturgie, he stated with commendable honesty, concerning the Mass as most Catholics know it today: “To tell the truth it is a different liturgy of the Mass. This needs to be said without ambiguity: the Roman Rite as we knew it no longer exists. It has been destroyed.” Even Archbishop Bugnini would have found it difficult to explain how something can be preserved and fostered by destroying it.